Acute Pancreatitis Treatment, Diagnosis & Cost

Renowned for its clinical excellence, PACE Hospitals stands among the best hospitals for acute pancreatitis treatment in Hyderabad, India. Our dedicated team of gastroenterologists, hepatobiliary surgeons, critical care specialists, radiologists, and dietitians delivers a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to diagnosing and managing all forms of acute pancreatitis using advanced tools and techniques. With a strong focus on early intervention, preventing complications, and restoring pancreatic function, we strive to ensure better outcomes and an improved quality of life for every patient.

Book an Appointment for Acute Pancreatitis Treatment

Acute Pancreatitis Treatment Online Appointment

Thank you for contacting us. We will get back to you as soon as possible. Kindly save these contact details in your contacts to receive calls and messages:-

Appointment Desk: 04048486868

WhatsApp: 8977889778

Regards,

PACE Hospitals

HITEC City and Madeenaguda

Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Oops, there was an error sending your message. Please try again later. Kindly save these contact details in your contacts to receive calls and messages:-

Appointment Desk: 04048486868

WhatsApp: 8977889778

Regards,

PACE Hospitals

HITEC City and Madeenaguda

Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Why Choose PACE Hospitals for Acute Pancreatitis Treatment?

Advanced Diagnostic Facilities: CT scan, MRI with MRCP, EUS, Pancreatic Function Tests (PFTs)

Top Gastroenterologists and Hepatobiliary Surgeons in Hyderabad

24x7 ICU-Based Critical Care for Moderate-to-Severe Pancreatitis with Minimally Invasive and Surgical Treatment Options

Affordable & Transparent Acute Pancreatitis Treatment with Insurance & Cashless Options

Acute Pancreatitis Diagnosis

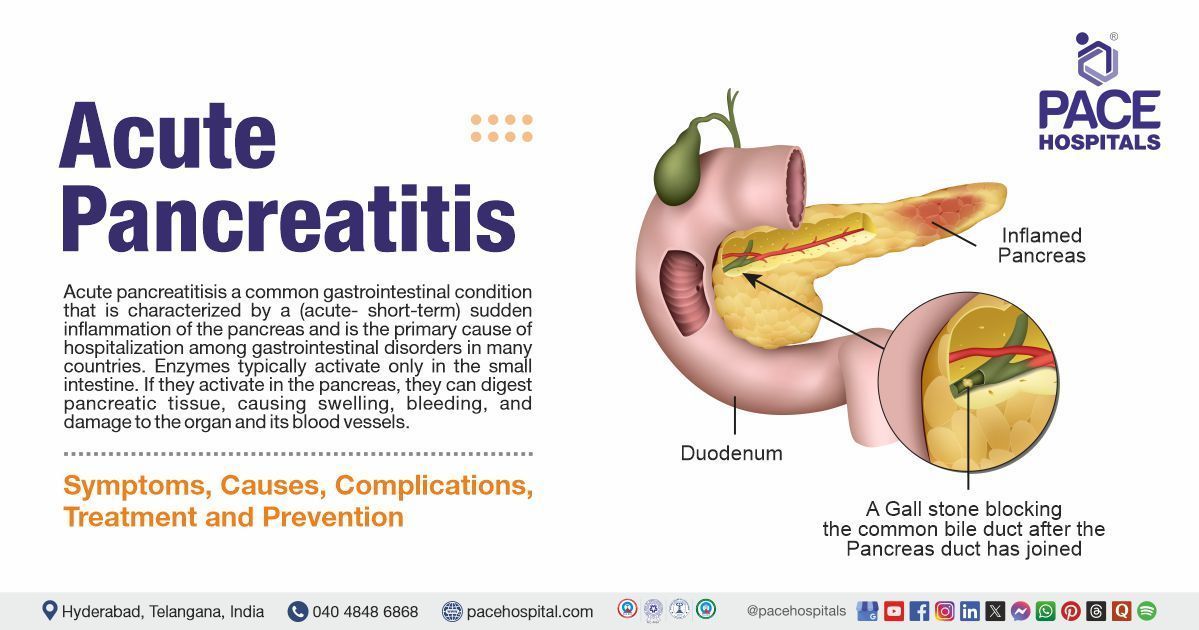

Initial clinical assessment is central to diagnosing acute pancreatitis, often presenting with sudden onset epigastric pain, nausea, and elevated pancreatic enzymes. The gastroenterologist evaluates clinical history and physical findings to determine the severity and etiology, commonly gallstones or alcohol, and guides decisions on imaging and hospitalization.

Timely diagnosis and appropriate management are crucial to prevent complications like necrosis, pseudocyst formation, and systemic organ failure. This overview outlines the main aspects of initial clinical evaluation, diagnostic tests including serum lipase and imaging, supportive treatment protocols, and differential diagnoses such as perforated ulcers or biliary colic.

Initial Evaluation and Detailed History

The first step in evaluating a patient with suspected acute pancreatitis is obtaining a detailed history, which can provide clues to the underlying aetiology. Key aspects to assess include:

- Gallstone Disease: Symptoms of biliary colic or imaging evidence of

gallstones or

choledocholithiasis (gallstones in the bile duct).

- Unexplained Weight Loss or New-Onset Diabetes: Potential indicators of

chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic tumors.

- Alcohol Use: A history of heavy alcohol consumption, a common cause of

pancreatitis.

- Medications: Certain medications, such as corticosteroids or diuretics, can induce pancreatitis.

- Trauma or Surgery: Prior trauma or surgery, especially abdominal, can lead to pancreatitis.

- Hypertriglyceridemia or Hypercalcemia: Elevated triglycerides or calcium levels may be associated with pancreatitis.

- Autoimmune Diseases or Family History: A family history of recurrent pancreatitis or autoimmune conditions may suggest an underlying genetic or immune-mediated cause.

- Physical Examination: The physical exam evaluates for abdominal tenderness, distension, and systemic signs of inflammation. In mild cases, findings may be limited to epigastric tenderness, while more severe cases may show signs of hypotension, tachycardia, or fever.

- Abdominal Palpation: Localized tenderness and guarding in the upper abdomen are common. Absence of bowel sounds may indicate paralytic ileus.

- Systemic Examination: The gastroenterologist looks for signs of systemic inflammation or organ failure (e.g., low oxygen saturation or confusion), which may point to severe acute pancreatitis.

Stages of Acute Pancreatitis

The 2012 revision of the Atlanta classification introduced a determinant-based approach to categorize acute pancreatitis (AP) severity, considering both organ failure and (peri) pancreatic necrosis. This framework aids clinicians in assessing disease severity and guiding treatment strategies. The following are the 4 stages of acute pancreatitis:

- Mild Acute Pancreatitis (MAP): Characterized by the absence of organ failure and (peri) pancreatic necrosis, MAP typically resolves within the first week without complications.

- Moderate Acute Pancreatitis: Defined by the presence of transient organ failure (lasting less than 48 hours) and/or sterile (peri) pancreatic necrosis, this stage may also involve local or systemic complications.

- Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP): SAP involves either persistent organ failure (lasting 48 hours or more) or infected (peri) pancreatic necrosis, indicating a more serious disease course.

- Critical Acute Pancreatitis: The most severe form, characterized by both infected (peri) pancreatic necrosis and persistent organ failure, often necessitating intensive care management.

This classification system enhances the ability to predict patient outcomes and standardize treatment approaches across clinical settings.

Revised Atlanta Classification for Acute Pancreatitis Diagnosis

The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires at least two of the following three criteria:

- Elevated Lipase or Amylase Levels: Lipase or amylase levels should be more than three times the normal upper limit. Elevated enzyme levels are critical indicators of pancreatic injury.

- Abdominal Pain Consistent with Pancreatitis: The patient must exhibit abdominal pain that is characteristic of pancreatitis, typically a severe, persistent pain in the epigastric region that may radiate to the back.

- Abdominal Imaging Consistent with Acute Pancreatitis: Imaging studies (such as ultrasound, CT Scan, or MRI) must show evidence of acute pancreatitis, such as pancreatic enlargement or fluid collections.

Acute Pancreatitis Diagnosis

After the initial assessment, gastroenterologists may select a single or a combination of the following tests to confirm the presence of acute pancreatitis:

Laboratory Evaluation

- Serum Amylase and Lipase

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs)

- Serum Triglycerides

- Serum Calcium

- Complete Blood Count (CBC)

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

- Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) and Creatinine

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG)

- Procalcitonin

Imaging studies

- Abdominal Ultrasound

- Computed Tomography (CT) with Intravenous Contrast

- Chest Radiograph (X-ray)

- CT with Pancreatic Protocol

Further Evaluation When the Cause is Unclear

- Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

- Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS)

- Computed Tomography (CT) with Pancreatic Protocol

Other tests

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

- Diagnostic ERCP

Laboratory Evaluation in Acute Pancreatitis

The laboratory workup for acute pancreatitis includes several routine tests to evaluate potential causes and assess severity:

- Serum Amylase and Lipase: These are the primary enzymes measured to diagnose acute pancreatitis. Lipase is more specific and remains elevated longer than amylase. A level more than three times the upper limit of normal supports the diagnosis.

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs): Tests such as ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin help determine if a biliary cause (like gallstones) is involved. Elevated ALT is particularly suggestive of gallstone pancreatitis.

- Serum Triglycerides: Elevated triglyceride levels (>1,000 mg/dL) can cause acute pancreatitis. This test is essential in patients without gallstones or alcohol use as a known cause.

- Serum Calcium: Hypercalcemia, often due to hyperparathyroidism or malignancy, is a less common but known cause of pancreatitis. Low calcium levels may also occur in severe pancreatitis and can indicate fat necrosis or a worse prognosis.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Leukocytosis (elevated white blood cell count) suggests inflammation or infection. Haematocrit is also monitored; a high level may indicate haemoconcentration and poor fluid status.

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP): CRP is an inflammatory marker that helps assess the severity of pancreatitis. Levels above 150 mg/L at 48 hours indicate more severe disease.

- Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) and Creatinine: These tests evaluate kidney function and hydration status. Elevated BUN at admission and rising levels within 24–48 hours are associated with increased mortality risk.

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG): Used to assess acid-base balance and oxygenation. Metabolic acidosis or hypoxemia may indicate severe pancreatitis or systemic complications.

- Procalcitonin: This biomarker can help differentiate between sterile and infected pancreatic necrosis. Elevated levels suggest bacterial infection and may guide antibiotic use.

Imaging Studies in Acute Pancreatitis

Imaging is a key component of acute pancreatitis diagnosis and management. Below are some of the commonly used imaging tests for this purpose:

- Abdominal Ultrasound: Abdominal ultrasound is a non-invasive, first-line imaging tool used to assess the pancreas and biliary system. It is particularly useful for detecting gallstones, choledocholithiasis, and bile duct dilatation, which are common causes of acute pancreatitis. Though limited in visualizing the pancreas during severe inflammation, it is crucial in identifying a biliary aetiology.

- Computed Tomography (CT) with Intravenous Contrast: Contrast-enhanced CT is performed when the diagnosis of pancreatitis is uncertain or complications like necrosis, abscess, or fluid collections are suspected. It is typically delayed until at least 48–72 hours after onset unless immediate complications are suspected, as early imaging may not reveal the full extent of the disease. It is also used to evaluate patients who do not improve with initial supportive care.

- Chest Radiograph (X-ray): A chest X-ray is often ordered in moderate to severe cases of pancreatitis to detect complications such as pleural effusions, atelectasis, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The presence of pleural effusions, especially on the left side, can indicate a more severe inflammatory response and correlates with increased morbidity and mortality.

- CT with Pancreatic Protocol: A specialized CT scan tailored for optimal visualization of the pancreas and surrounding tissues. It is used when patients fail to improve after standard treatment or show signs of deterioration. This imaging helps detect peripancreatic necrosis, infected collections, and other complications, aiding in guiding minimally invasive or surgical intervention if needed.

Further Evaluation When the Cause is Unclear

When the initial evaluation does not reveal a clear cause, further diagnostic measures may be required:

- Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): MRCP is a non-invasive imaging technique that does not require contrast and can provide detailed views of the biliary and pancreatic ducts. However, MRCP may have limited sensitivity for detecting smaller biliary stones and chronic pancreatitis.

- Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS); EUS is preferred for detecting small biliary stones and assessing chronic pancreatitis. It is more sensitive than MRCP, and while it is invasive, it provides a higher resolution image.

- Computed Tomography (CT) with Pancreatic Protocol: If MRCP or EUS is unavailable, a CT scan with a pancreatic protocol may be used to further evaluate the pancreas and surrounding structures.

Other tests

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): ERCP is typically not performed as a diagnostic tool unless there is a clear indication for therapeutic intervention.

- Diagnostic ERCP: ERCP is reserved for patients with abnormal findings on MRCP or EUS who require therapeutic intervention, such as stone removal, stent placement, or bile duct drainage. This approach ensures that acute pancreatitis is diagnosed accurately, underlying causes are identified, and appropriate treatment is initiated promptly.

Differential Diagnosis for Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis can present with symptoms such as epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and elevated pancreatic enzymes, which overlap with other abdominal conditions. The following are potential differential diagnoses:

- Severe Acute Cholecystitis: Cholecystitis, especially in the presence of gallstones, can present with similar abdominal pain and nausea, especially in the upper abdomen. Ultrasound or CT imaging can help differentiate by showing gallstones and signs of inflammation in the gallbladder.

- Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD): Peptic ulcers can cause upper abdominal pain, often exacerbated by eating, which can mimic acute pancreatitis. Endoscopy and the presence of gastric ulcers on imaging help distinguish PUD from pancreatitis.

- Gastrointestinal Perforation: A perforated bowel or stomach ulcer can present with acute abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and systemic symptoms. Free air on abdominal X-ray or CT imaging confirms the diagnosis of perforation, distinguishing it from pancreatitis.

- Biliary Colic: Biliary colic, caused by temporary bile duct obstruction (often due to gallstones), can lead to similar symptoms, including epigastric pain and nausea. Ultrasound can confirm the presence of gallstones, differentiating it from pancreatitis.

- Acute Gastroenteritis: Acute gastroenteritis can cause abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever, which overlap with acute pancreatitis. Stool cultures and imaging can help confirm gastroenteritis, particularly if diarrhoea is present.

These conditions must be considered when diagnosing acute pancreatitis, and appropriate imaging, clinical evaluation, and lab tests are essential to make an accurate diagnosis.

Treatment for acute pancreatitis focuses on managing symptoms, supporting the pancreas, and preventing complications, including:

Conservative Treatments

- Aggressive Intravenous Fluid Resuscitation:

- Pain Management

- Early Enteral Nutrition

- Monitoring and Supportive Care

Minimally Invasive Treatments

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

- Percutaneous Catheter Drainage (PCD)

- Endoscopic Transluminal Necrosectomy

- Minimally Invasive Necrosectomy

Surgical Treatments

- Minimally Invasive Necrosectomy

- Open Surgical Necrosectomy

- Cholecystectomy

Conservative Treatments

Conservative management is typically chosen in cases of mild to moderately severe acute pancreatitis, where there are no signs of infected necrosis or persistent organ failure. Below are key conservative management strategies, typically selected when the patient is clinically stable and lacks evidence of severe complications:

- Aggressive Intravenous Fluid Resuscitation: Fluid replacement using isotonic crystalloids (usually lactated Ringer's solution) within the first 24 hours is critical in managing acute pancreatitis. It helps restore intravascular volume, maintain organ perfusion, and reduce pancreatic necrosis. Monitoring for fluid overload is essential, especially in elderly or comorbid patients.

- Pain Management: Pain in acute pancreatitis is often severe and persistent. Painkillers such as morphine or hydromorphone are preferred for effective relief. Adequate pain control also reduces stress-related physiological complications.

- Early Enteral Nutrition: Patients with mild pancreatitis can resume oral feeding as tolerated, often within 24–48 hours. In moderate to severe cases, early enteral feeding via the nasogastric or nasojejunal route helps prevent gut mucosal atrophy, bacterial translocation, and infectious complications.

- Monitoring and Supportive Care: Patients require close monitoring of vital signs, urine output, electrolytes, and organ function. Management of complications like hypoxia, renal impairment, or hyperglycaemia may be needed. ICU care may be indicated for persistent organ failure or systemic complications.

Minimally Invasive Treatments

Below are key minimally invasive treatment options, typically selected when patients develop local complications such as infected necrosis or symptomatic fluid collections that do not respond to conservative management:

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): It is indicated in patients with biliary pancreatitis complicated by cholangitis or persistent bile duct obstruction. ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone removal relieves obstruction and prevents worsening inflammation. It's most beneficial when performed within 24–48 hours in high-risk patients.

- Percutaneous Catheter Drainage (PCD): It is used in cases of infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic fluid collections. PCD is image-guided and allows drainage without immediate surgery. It’s part of the "step-up" approach, often reducing the need for open necrosectomy.

- Endoscopic Transluminal Necrosectomy: For walled-off necrosis (usually after 4 weeks), endoscopic drainage through the stomach or duodenum may be performed using lumen-apposing metal stents. It allows necrosectomy with less morbidity than open surgery and is performed under sedation.

- Minimally Invasive Necrosectomy: This includes laparoscopic or video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement. It is used in selected patients with infected necrosis not amenable to drainage. Compared to open surgery, it offers shorter recovery and fewer complications.

Surgical Treatments

Below are key surgical treatment options, typically selected when patients have severe or persistent complications such as infected pancreatic necrosis, that do not respond to conservative or minimally invasive approaches:

- Open Surgical Necrosectomy: This is a last-resort option for patients with persistent or worsening infected necrosis despite less invasive methods. It involves the surgical removal of dead tissue through an abdominal incision. Risks include bleeding, fistulas, and prolonged recovery.

- Cholecystectomy: In cases of gallstone-induced pancreatitis, elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy is performed after recovery to prevent recurrence. In mild cases, it is done during the same hospitalization, while in severe cases, it's delayed until inflammation resolves.

Acute Pancreatitis Treatment Cost in Hyderabad, India

The

cost of Acute Pancreatitis Treatment in Hyderabad generally ranges from ₹25,000 to ₹1,80,000 (approximately US $300 – US $2,170).

The exact price varies depending on several factors such as the severity of pancreatitis (mild, moderate, or severe), need for ICU care, imaging tests (ultrasound, CT scan, MRI), duration of hospitalization, requirement for endoscopic ERCP procedures, complications like necrosis or infection, surgeon/gastroenterologist expertise, and the hospital facilities chosen — including cashless treatment options, TPA corporate tie-ups, and assistance with medical insurance approvals wherever applicable.

Cost Breakdown According to Type of Acute Pancreatitis Treatment

- Mild Acute Pancreatitis (Medical Management Only) – ₹25,000 – ₹55,000 (US $300 – US $660)

- Moderate Acute Pancreatitis (IV Fluids, Pain Management, Monitoring) – ₹45,000 – ₹1,20,000 (US $540 – US $1,445)

- Severe Acute Pancreatitis (ICU Care + Organ Support) – ₹1,00,000 – ₹1,80,000 (US $1,200 – US $2,170)

- ERCP for Gallstone-Induced Pancreatitis – ₹40,000 – ₹95,000 (US $480 – US $1,145)

- Endoscopic or Surgical Pancreatic Necrosectomy –

₹1,20,000 – ₹1,80,000 (US $1,445 – US $2,170)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Acute Pancreatitis

What is recurrent acute pancreatitis?

Recurrent acute pancreatitis is defined as two or more distinct episodes of acute pancreatitis, separated by at least three months or a clear recovery period, often caused by unresolved risk factors like gallstones, alcohol, or genetic predispositions.

What are the signs of acute pancreatitis?

Key signs include sudden-onset severe epigastric pain (often radiating to the back), nausea, vomiting, abdominal tenderness, and in severe cases, fever, hypotension, or signs of shock.

Which Is the Best Hospital for Acute Pancreatitis Treatment in Hyderabad, India?

PACE Hospitals, Hyderabad, is considered one of the most trusted and advanced centres for the treatment of acute pancreatitis, both mild and life-threatening forms.

Our expert team of gastroenterologists, hepatologists, endoscopists, intensivists, and GI surgeons is highly experienced in managing complex pancreatitis cases using evidence-based protocols, real-time monitoring, advanced endoscopic interventions, and organ-supportive care.

With fully equipped ICU units, cutting-edge diagnostic imaging, 24×7 emergency care, and advanced ERCP and endoscopic facilities, PACE Hospitals ensures safe, accurate, and timely treatment — supported by cashless facilities, TPA corporate tie-ups, and assistance with medical insurance processing for eligible patients.

What are the 2 most common causes of acute pancreatitis?

The two leading causes are gallstones (which block the pancreatic duct) and chronic alcohol use, together accounting for 70–80% of cases globally.

When does acute pancreatitis become chronic?

Acute pancreatitis may evolve into chronic pancreatitis after repeated attacks lead to irreversible damage, fibrosis, and pancreatic insufficiency, typically over months or years of ongoing inflammation.

What Is the Cost of Acute Pancreatitis Treatment at PACE Hospitals, Hyderabad?

At PACE Hospitals, Hyderabad, the cost of Acute Pancreatitis Treatment typically ranges from ₹25,000 to ₹1,60,000 and above (approximately US $300 – US $1,930), depending on:

- Severity of pancreatitis (mild, moderate, severe)

- Whether ICU monitoring or ventilator/organ support is required

- Diagnostic tests (blood tests, ultrasound, CT scan, MRI)

- Requirement for ERCP or endoscopic interventions

- Presence of complications such as necrosis, infection, or organ failure

- Duration of hospitalization

- Gastroenterologist or surgical expertise

- Additional nutritional support or specialized medications

For mild cases, costs fall in the lower range. For gallstone-induced or severe pancreatitis needing ICU or ERCP, costs move toward the higher side. After a comprehensive evaluation, imaging review, and severity grading, our gastroenterology team provides a personalized treatment plan and accurate cost estimate based on your clinical condition and medical needs.

What is the acute pancreatitis score?

The acute pancreatitis score refers to clinical scoring systems like Ranson’s criteria, APACHE II, or the BISAP score used to predict the severity, complications, and mortality risk in patients with acute pancreatitis.

What is the Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis?

The revised Atlanta classification (2012) stratifies acute pancreatitis into mild, moderate, and severe based on the presence of organ failure and pancreatic necrosis; it helps guide diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

Which enzyme is more specific for acute pancreatitis?

Serum lipase is more specific and sensitive than amylase for diagnosing acute pancreatitis, remaining elevated longer and providing more diagnostic accuracy.

Can I drink alcohol in moderation after acute pancreatitis?

No, alcohol, even in moderation, should be strictly avoided after an episode of acute pancreatitis, as it can trigger recurrence and increase the risk of chronic pancreatitis.

Can laparoscopic cholecystectomy prevent recurrent idiopathic acute pancreatitis?

In patients with occult biliary disease, laparoscopic cholecystectomy can reduce the risk of recurrent idiopathic acute pancreatitis, particularly if gallbladder sludge or microlithiasis is suspected.