Gastroparesis - Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment & Prevention

PACE Hospitals

Gastroparesis definition

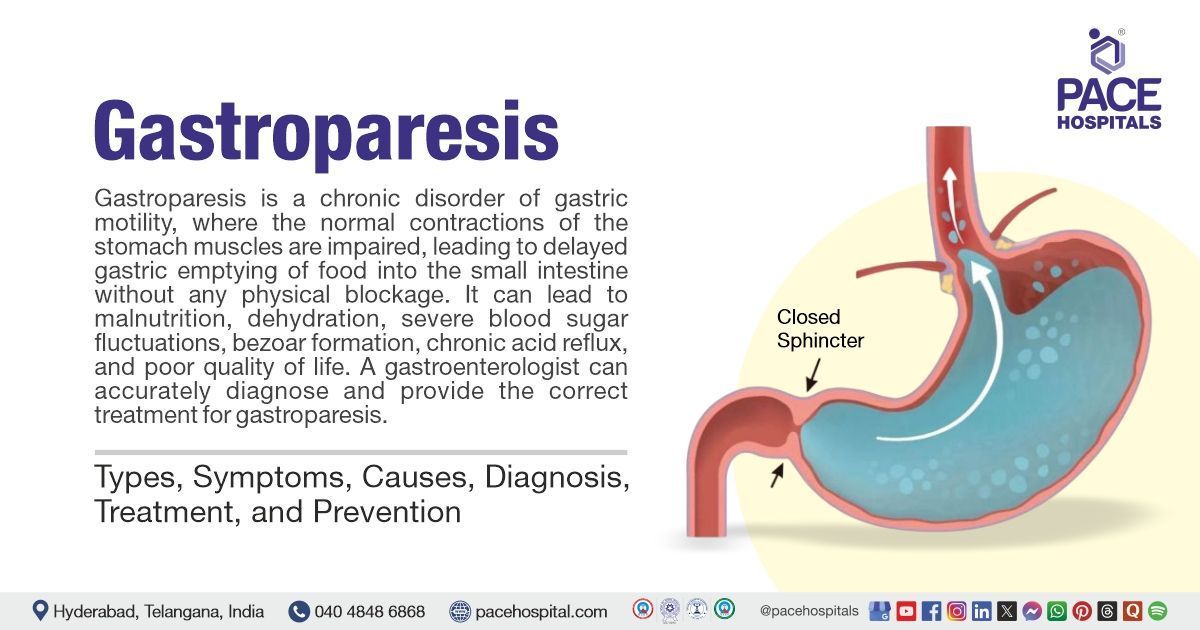

Gastroparesis is a chronic disorder of gastric motility, where the normal contractions of the stomach muscles are impaired, leading to delayed gastric emptying (DGE) of food into the small intestine without any physical blockage. For clinical diagnosis, symptoms should last for at least 3 months. Common symptoms include nausea, vomiting of undigested food, bloating, early satiety (feeling full quickly), abdominal pain, heartburn, and unintended weight loss.

The main causes include diabetes, surgical injury to the stomach’s nerves, certain medications, neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease, autoimmune diseases, and sometimes the cause is unknown (idiopathic gastroparesis). Complications can involve malnutrition, dehydration, severe blood sugar fluctuations, bezoar formation (hardened food masses), chronic acid reflux, and poor quality of life.

A

gastroenterologist, a doctor specialised in digestive system diseases, can accurately diagnose and provide the correct treatment for gastroparesis.

Gastroparesis meaning

The word gastroparesis originates from the two Greek words

- "gastro" meaning "stomach"

- "-paresis" meaning "partial paralysis" or "weakness".

Thus, gastroparesis means "partial paralysis of the stomach," reflecting the condition’s hallmark feature: delayed stomach emptying due to weakened or impaired muscle contractions, not a physical blockage.

Gastroparesis Prevalence

Gastroparesis prevalence Worldwide

The global prevalence of gastroparesis, a condition characterised by delayed stomach emptying, is estimated to be approximately 1.8% of the population, according to some studies, although this can vary. Studies in the US and UK have reported rates ranging from 13.8 to 267.7 per 100,000 adults. However, the exact prevalence, especially in regions such as Asia, remains unknown, mainly due to the limited research available.

Gastroparesis prevalence in India

In India, the exact prevalence of gastroparesis in the general population remains unclear due to the lack of large-scale, population-based studies. However, hospital-based and clinic-based reports suggest that gastroparesis is more common among people with diabetes, particularly those with poor glycaemic control. Small studies have reported symptoms of gastroparesis in approximately 5–12% of Indian diabetic patients. This is consistent with global findings, where the condition is more frequent in women and often underdiagnosed.

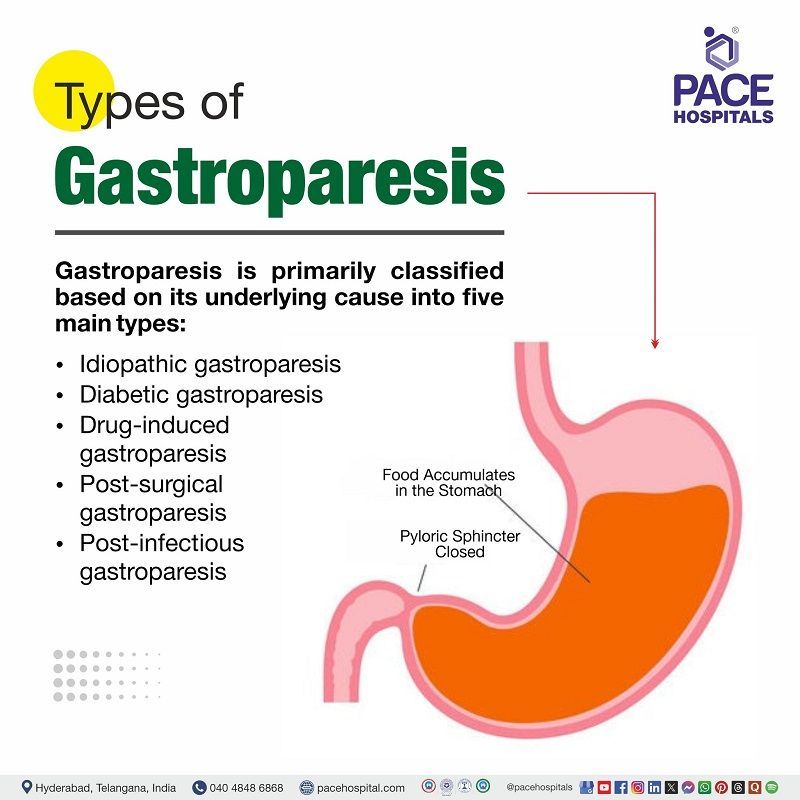

Gastroparesis Types

Gastroparesis is primarily classified based on its underlying cause into five main types:

- Idiopathic gastroparesis

- Diabetic gastroparesis

- Drug-induced gastroparesis

- Post-surgical gastroparesis

- Post-infectious gastroparesis

Idiopathic gastroparesis

This type of gastroparesis is diagnosed when no clear cause, such as diabetes or surgery, can be identified, despite thorough clinical evaluation. This is the most common type in some studies, reflecting the frequency with which a specific cause cannot be determined.

Diabetic gastroparesis

Occurs as a complication of long-standing or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Chronic hyperglycaemia damages the vagus nerve and other components of the enteric nervous system, leading to impaired gastric motility. Both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes can be affected.

Drug-induced gastroparesis

Drug-induced gastroparesis is a type of secondary gastroparesis caused by certain medications that slow stomach emptying. Drugs like opioids, some antidepressants, blood pressure medicines, and GLP-1 receptor agonists can interfere with stomach nerves or muscles. Symptoms usually improve if the responsible drug is stopped or replaced.

Post-surgical gastroparesis

Postsurgical gastroparesis arises following surgical procedures that can injure the vagus nerve or alter normal gastric anatomy, such as fundoplication, vagotomy, esophagectomy, or bariatric and duodenal surgeries.

Post-infectious gastroparesis

Post-infectious gastroparesis develops after an acute gastrointestinal infection, most commonly viral (e.g., Norovirus, Rotavirus, Cytomegalovirus). Less commonly, bacterial infections can trigger it. Symptoms may sometimes improve over months to years, making this type more likely to have a partially reversible course.

Gastroparesis Symptoms

Gastroparesis presents with a range of gastrointestinal symptoms that result from delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction. The clinical presentation can vary in severity and often overlaps with other gastrointestinal disorders, making diagnosis challenging

The following are the symptoms of gastroparesis:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Feeling of stomach fullness

- Bloating

- Belching

- Upper abdomen pain

- Heartburn

- Loss of appetite

- Changes in blood sugar levels

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms of gastroparesis, caused by delayed gastric emptying. Food remaining in the stomach too long leads to a buildup and distention, triggering nausea and sometimes vomiting of undigested food hours after eating. These symptoms are often worse after meals and can significantly affect quality of life, especially in cases of diabetic gastroparesis.

Feeling of stomach fullness

One of the main signs of gastroparesis is a feeling of fullness in the stomach, which is sometimes referred to as "feeling full soon after starting a meal" (early satiety) or "feeling full long after eating" (postprandial fullness). This occurs because food stays in the stomach for longer lengths of time due to gastroparesis, which causes the stomach muscles to transport food into the small intestine considerably more slowly than usual. The accumulation of undigested food causes the stomach to expand, which initiates and prolongs the feeling of fullness.

Bloating

Impaired gastric motility leads to prolonged retention of gas and contents in the stomach and small intestine, causing a sensation of bloating and visible distension. This symptom reflects both delayed emptying and impaired gastric accommodation.

Belching

Due to gastroparesis, the stomach empties food more slowly than normal, causing food and gas to accumulate and leading to sensations of fullness and excessive belching.

Upper abdomen pain

Upper abdominal pain in gastroparesis is a consequence of retained gastric contents, abnormal motility, and heightened sensory responses.

Heartburn

When gastric emptying is delayed, as in gastroparesis, food and stomach acid remain in the stomach longer than normal. This prolonged retention increases the likelihood of acid and food contents refluxing back into the esophagus, causing heartburn, regurgitation, and GERD-like symptoms.

Loss of appetite

People with gastroparesis often eat less, which can cause unintentional weight loss and increase the risk of malnutrition. The persistent sensation of fullness and discomfort after eating discourages normal eating patterns, making loss of appetite a hallmark symptom of this condition.

Changes in blood sugar levels

This is a common problem in people with gastroparesis, especially those with diabetes. This happens because the stomach empties food slowly and at unpredictable times. As a result, sugars from food may enter the bloodstream much later than expected. This can cause blood sugar to go too high if the food is absorbed suddenly, or too low if insulin was taken but the food hasn’t been digested yet. These ups and downs in blood sugar can make diabetes harder to manage. If a patient has diabetes and notices frequent changes in their blood sugar, especially after meals, it could be a sign of gastroparesis.

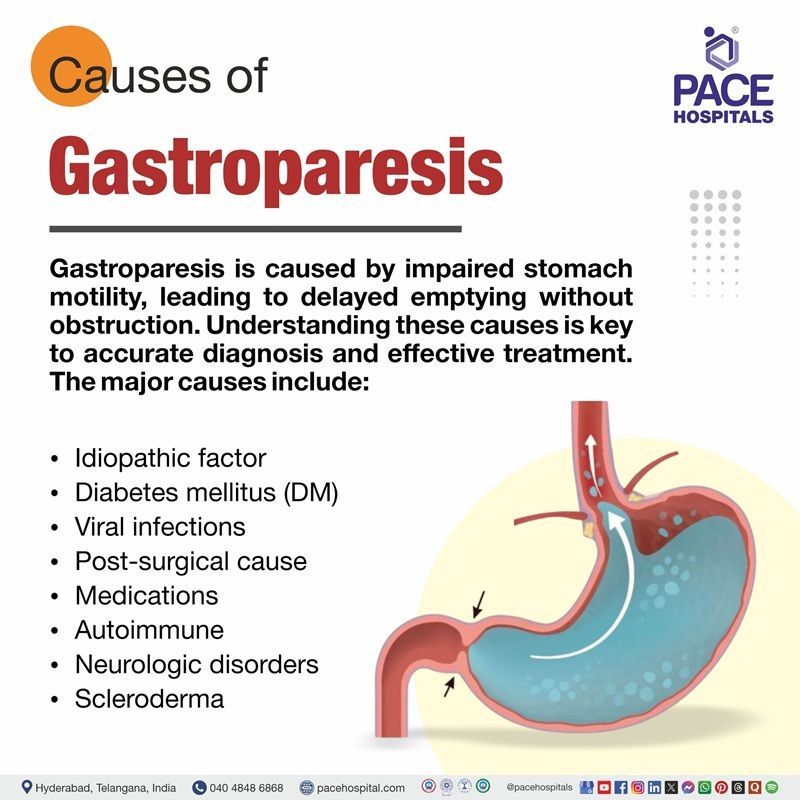

Gastroparesis Causes

Gastroparesis occurs when the normal motility of the stomach is impaired, leading to delayed gastric emptying without an obstruction. Numerous neurological, muscular, metabolic, and iatrogenic factors can interfere with the stomach's ability to contract in coordination. Accurate diagnosis, successful treatment, and better patient outcomes all depend on an understanding of these underlying causes of gastroparesis.

The major causes of gastroparesis are as follows:

- Idiopathic factor

- Diabetes mellitus (DM)

- Viral infections

- Post-surgical cause

- Medications

- Autoimmune

- Neurologic disorders

- Scleroderma

Idiopathic factor

When gastroparesis occurs without a known cause is called idiopathic gastroparesis.

Diabetes mellitus (DM)

Diabetes mellitus, especially when poorly controlled, can damage the vagus nerve and enteric nervous system, impairing gastric motility. Chronic hyperglycemia leads to neuropathy, which disrupts the normal coordination of stomach muscles, resulting in delayed gastric emptying. This is also known as diabetic gastroparesis.

Viral infections

Viral infections, particularly those caused by norovirus, rotavirus, and Epstein-Barr virus, are recognised triggers for post-infectious gastroparesis. These viruses cause inflammation and damage to the stomach lining, the enteric nervous system, or the interstitial cells of Cajal (pacemaker cells of the gut). This injury may disrupt the stomach's normal electrical and muscular activity, leading to impaired contractions and delayed gastric emptying. While usually transient, in some people, post-viral damage might lead to chronic gastroparesis.

Post-surgical cause

Post-surgical gastroparesis can happen after procedures like vagotomy, gastric resection or drainage, fundoplication, esophagectomy, gastric bypass, Whipple procedure, and heart or lung transplantation. These surgeries might damage the vagus nerve or interrupt gastric innervation. This can impair the stomach’s ability to contract and empty food properly.

Medications

Drugs that impair gastric motility include opioids, anticholinergics, tricyclic antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, cannabinoids, GLP-1 receptor agonists and certain overactive bladder medications. Drug-induced gastroparesis may improve upon discontinuation.

Autoimmune (autonomic gastroparesis)

Autoimmune conditions can cause gastroparesis by generating antibodies that attack the enteric nervous system or interstitial cells of Cajal, disrupting normal gastric motility. Examples include autoimmune dysautonomia and systemic autoimmune diseases.

Neurologic disorders

Neurological diseases such as Parkinson's disease, stroke, and multiple sclerosis can affect the autonomic control of gastric motility, resulting in delayed stomach emptying. These disorders affect the neurological connections that control stomach contractions.

Scleroderma

Scleroderma is a connective tissue condition that may induce fibrosis and atrophy of the smooth muscle in the stomach wall, impairing motility and leading to scleroderma gastroparesis. It may also affect the nerves controlling gastric function.

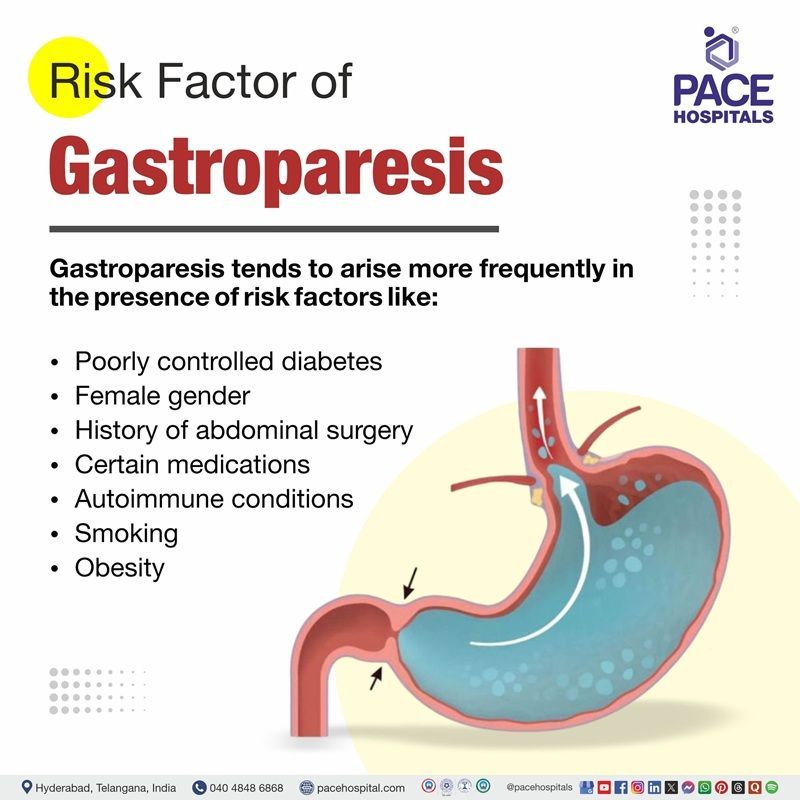

Gastroparesis Risk Factors

While gastroparesis is primarily associated with certain underlying conditions, many risk factors can increase the likelihood of its development. These factors do not directly cause delayed gastric emptying, but they can impair nerve function or disrupt normal digestion. This can lead to the onset or worsening of gastroparesis.

- Poorly controlled diabetes

- Female gender

- History of abdominal surgery

- Certain medications

- Autoimmune conditions

- Smoking

- Obesity

Poorly controlled diabetes

Poorly managed diabetes, especially long-standing type 1 or type 2, is the strongest risk factor for gastroparesis. High levels of blood sugar damage the vagus nerve, which controls stomach muscle contractions, and also harm the stomach’s pacemaker cells. This leads to weak or irregular contractions, slowing down gastric emptying. Studies show that about one-third of people with chronic diabetes may develop some degree of gastroparesis.

Female gender

Women are affected up to four times more often than men. Research suggests that female hormones may slow stomach emptying. These effects are especially noticeable during pregnancy or in the luteal phase (LP) of the menstrual cycle.

History of abdominal surgery

Operations involving the stomach or esophagus, such as bariatric surgery, fundoplication, etc., can damage the vagus nerve or alter stomach anatomy. Injury to this nerve disrupts communication between the brain and stomach, weakening contractions needed for food movement. Surgical scarring or changes in stomach shape can also mechanically impair gastric emptying.

Certain medications

Several commonly used drugs can slow stomach contractions or delay gastric emptying. These include opioids (for pain), anticholinergics (used for allergies or bladder problems), tricyclic antidepressants, and newer diabetes drugs like GLP-1 receptor agonists. When these medications interfere with stomach muscle or nerve function, they can trigger or worsen symptoms of gastroparesis.

Autoimmune conditions

Autoimmune diseases such as lupus or scleroderma can damage nerves, connective tissue, and smooth muscle of the gastrointestinal tract. Inflammation and autoimmune reactions can impair the vagus nerve and stomach muscle layers, reducing motility. Patients with these conditions often experience many digestive complications, and gastroparesis is one of the more disabling outcomes.

Smoking

Tobacco use has been linked to delayed gastric emptying in clinical studies. Tobacco affects the nervous system, including vagal nerve activity, and can impair the coordination of stomach contractions. Smoking may also aggravate microvascular disease by lowering blood supply to the nerves and muscles that control stomach motility, particularly in diabetic patients.

Obesity

Excess body weight is associated with hormonal and metabolic changes that impair gastric emptying. Obesity often coexists with diabetes, further amplifying risk. Studies suggest that increased fat tissue produces cytokines and alters gut hormone signalling, which may weaken gastric muscle contractions. Additionally, obesity increases the possibility of needing abdominal surgery, which itself is a risk factor.

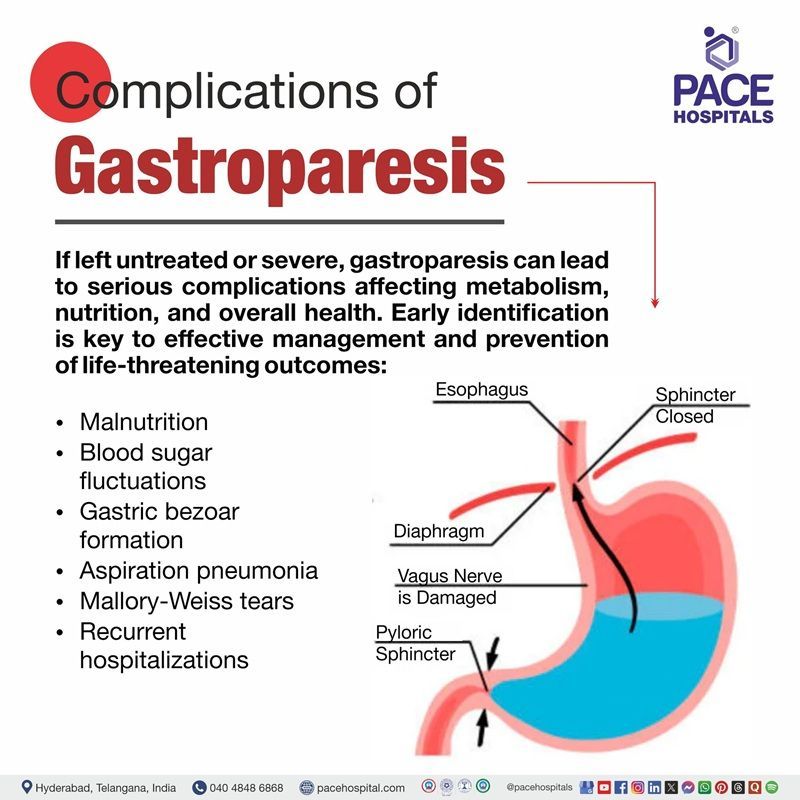

Gastroparesis Complications

Complications can develop when gastroparesis remains untreated or becomes severe and persistent. The impaired gastric emptying associated with gastroparesis can lead to a range of serious medical issues that affect metabolism, nutrition, and overall health. Identifying these complications of gastroparesis is important for management and preventing life-threatening consequences. The following are the main complications of gastroparesis:

- Malnutrition

- Blood sugar fluctuations

- Gastric bezoar formation

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Mallory-Weiss tears

- Recurrent hospitalisations

Malnutrition

Gastroparesis delays or disrupts normal stomach emptying, making it difficult to ingest and absorb adequate nutrients. Persistent nausea, vomiting, early satiety, or loss of appetite lead to reduced caloric and nutrient intake. Ongoing symptoms can result in significant weight loss, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and protein-energy malnutrition.

Blood sugar fluctuations

Because food does not leave the stomach at a predictable rate, glucose enters the bloodstream unpredictably after eating. This is especially problematic for people with diabetes, as it leads to alternating episodes of high and low blood sugar. Poor glycaemic control can further slow stomach emptying, resulting in a vicious cycle.

Gastric bezoar formation

Gastric bezoar formation occurs when solid masses of undigested food accumulate due to prolonged gastric stasis. These bezoars can obstruct the stomach outlet or cause ulcers, nausea, and vomiting, which are common bezoar symptoms in gastroparesis.

Aspiration pneumonia

Delayed stomach emptying increases the risk that food or gastric contents may reflux into the esophagus and potentially enter the respiratory tract, especially during vomiting or recumbency. This aspiration can cause pneumonia or other serious lung infections.

Mallory-Weiss tears

Patients with poorly controlled gastroparesis frequently have severe vomiting and repetitive retching, which can result in Mallory-Weiss tears or mucosal lacerations at the gastro-oesophageal junction. The upper gastrointestinal tract may bleed as a result of these tears.

Recurrent hospitalizations

Recurrent hospitalizations result from the ongoing nature of gastroparesis and its complications. Severe symptoms such as dehydration, persistent vomiting, nutritional deficiencies, and unstable blood glucose often require emergency care or hospital treatment.

Each of these complications directly arises from the impaired gastric motility that defines gastroparesis, leading to stasis, nutritional problems, and heightened comorbidity risks.

Gastroparesis Diagnosis

To diagnose gastroparesis, gastroenterologists generally use clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and specialized gastric emptying tests to check the severity of delayed gastric motility and eliminate other causes. A gastroenterologist handles both diagnosis and management.

The following are the steps commonly included in the diagnostic criteria for gastroparesis:

- Medical history

- Physical examination

- Laboratory tests

- Blood test

- Urine tests

- Imaging studies

- Upper gastrointestinal (GI) series

- Gastric ultrasonography

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Endoscopic evaluation

- Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

- Tests to measure stomach emptying

- Scintigraphic gastric emptying scan (GES)

- Gastric emptying breath test (GEBT)

- Antroduodenal manometry

- Wireless motility capsule (WMC)

Gastroparesis Treatment

The goal of gastroparesis treatment is to alleviate symptoms, improve stomach emptying, and prevent complications using a personalised, step-by-step approach. Dietary and lifestyle changes are usually the first step in treatment, however, drugs to enhance stomach motility or regulate symptoms may also be used. The type of treatment depends on how serious the ailment is, the nutritional needs, and the underlying causes. More severe or resistant cases require extensive medical, endoscopic, or surgical procedures supervised by a gastroenterologist. Gastroparesis treatment includes:

- Non-pharmacological therapy

- Pharmacological therapy

- Endoscopic management

- Surgical interventions

Non-pharmacological therapy

- Lifestyle and dietary modifications

- Controlling blood glucose levels

- Avoiding drugs that cause gastroparesis

- Nutritional support

- Patient education

Pharmacological therapy

- Antiemetics

- Prokinetic agents

- Dopamine-D2 antagonist

- Macrolide antibiotic

- Pain medicines

- Antidepressants

Endoscopic management

- Gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy (G-POEM)

- Pyloric botulinum toxin injection

- Pyloric balloon dilation

Surgical interventions

- Jejunostomy tube feeding

- Gastric electrical stimulation (GES)

- Venting gastrostomy

Why Choose PACE Hospitals?

Expert Super Specialist Doctors

Advanced Diagnostics & Treatment

Affordable & Transparent Care

24x7 Emergency & ICU Support

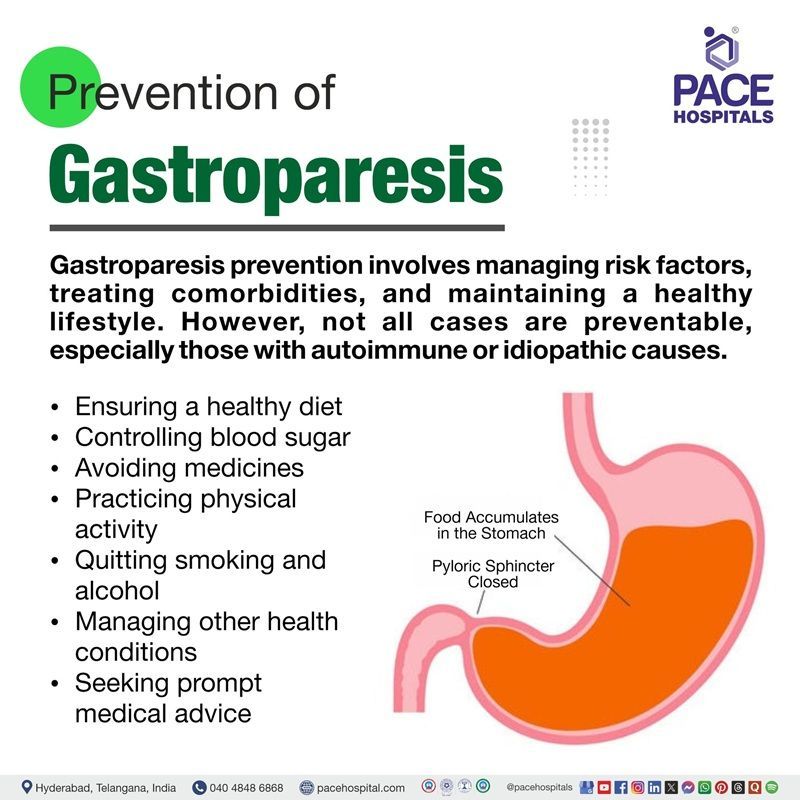

Gastroparesis Prevention

Gastroparesis prevention focuses on reducing underlying risks, addressing comorbid diseases, and keeping a healthy lifestyle to support normal stomach function. Because not all cases can be prevented (autoimmune or idiopathic reasons). The following measures are commonly recommended to prevent or minimize the development of gastroparesis:

- Ensuring a healthy diet

- Controlling blood sugar

- Avoiding medicines

- Practising physical activity

- Quitting smoking and alcohol

- Managing other health conditions

- Seeking prompt medical advice

Ensuring a healthy diet

A balanced, nutrient-rich diet supports overall digestive health and may help maintain proper gastric motility. Avoiding foods low in fat and fibre, which slow gastric emptying, and eating smaller (eat five or six small, nutrition-rich meals a day instead of two or three large meals), more frequent meals can decrease the strain on the stomach. Maintaining a healthy body mass index (BMI) with proper nutrition can also decrease the risk of conditions like diabetes and obesity, which are associated with gastroparesis.

Controlling blood sugar

Patients with poorly controlled diabetes are the leading known cause of gastroparesis. Persistently high blood sugar levels damage the vagus nerve and the stomach’s pacemaker cells, impairing motility. Keeping blood glucose levels under control through medication, diet, and exercise reduces nerve damage and lowers the risk of developing diabetic gastroparesis.

Avoiding medicines

Some drugs, including anticholinergics, opioids, and some antidepressants, slow down stomach emptying. Avoiding unnecessary use of these drugs or using safer alternatives, when possible, can help prevent medication-induced gastroparesis. If such medications are essential, close monitoring by a physician can minimise risk.

Practicing physical activity

Regular physical activity, like walking after meals, helps stimulate digestion and move food more efficiently through the digestive system, which may lower the chance of delayed gastric emptying and relieve mild symptoms.

Quitting smoking and alcohol

Smoking and alcohol both have negative effects on stomach motility. Alcohol, in particular, can delay gastric emptying and worsen dehydration, while both substances can harm the digestive tract. Avoiding or quitting them supports healthy stomach function.

Managing other health conditions

Chronic illnesses like autoimmune disorders or diabetes can increase the risk for gastroparesis. Managing these conditions with the help of the doctor lowers the risk of nerve damage that can lead to delayed stomach emptying.

Seeking prompt medical advice

The presence of symptoms such as frequent nausea, vomiting, or feeling full quickly, it's important to see a doctor early. This allows for timely diagnosis and treatment. Early medical intervention can significantly reduce the risk of complications and help manage or even prevent progression to severe gastroparesis.

Difference Between Gastric outlet obstruction and Gastroparesis

Gastric outlet obstruction vs Gastroparesis

Both gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) and gastroparesis cause problems with stomach emptying and can result in similar symptoms. However, their underlying causes and mechanisms are fundamentally different. Distinguishing between the two is essential for treatment strategies. Below are the key differences between GOO and GP:

| Parameters | Gastric outlet obstructions | Gastroparesis |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Mechanical blockage at the pylorus or duodenum, preventing gastric emptying | Delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction |

| Etiology | Tumors (gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer), peptic ulcer disease, strictures, bezoars | Diabetes mellitus (most common), idiopathic, post-surgical, medications (e.g., opioids, anticholinergics) |

| Pathophysiology | Physical obstruction prevents food passage | Impaired gastric motility due to nerve or muscle dysfunction |

| Symptoms | Nausea, vomiting (often large, undigested food), epigastric fullness, weight loss | Nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating, upper abdominal discomfort |

| Diagnosis | Upper GI endoscopy, barium meal, and CT scan to locate obstruction | Gastric emptying scintigraphy, exclusion of mechanical obstruction by endoscopy or imaging |

| Treatment | Relieve obstruction (endoscopic dilation, stenting, or surgery) | Dietary changes, prokinetic medications, and sometimes gastric electrical stimulation |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Gastroparesis

How to overcome gastroparesis?

Management of gastroparesis is multidisciplinary and typically focuses on alleviating symptoms, correcting nutritional deficiencies, and improving gastric emptying. Initial strategies involve making dietary modifications, such as frequent meals that are low in fat and fibre and eating small amounts. Optimising control of underlying conditions (for example, maintaining good glycemic control in patients with diabetes) is also essential. Severe or refractory cases may require enteral nutrition via a jejunostomy tube, and rarely, parenteral nutrition.

What are the medications for gastroparesis?

Gastroparesis medications include prokinetic agents (to enhance gastric emptying) and antiemetics (to control nausea and vomiting). A dopamine-D2 antagonist may be used. Other treatments under investigation or used off-label include 5-HT4 agonists and centrally acting antidepressants as symptom modulators. For refractory symptoms, gastric electrical stimulation may be considered.

What is the gastroparesis life expectancy?

Gastroparesis itself does not usually reduce life expectancy significantly, but it can lead to considerable morbidity and negatively impact quality of life. Severe complications such as malnutrition, dehydration, and poor glycaemic control can be life-threatening if not appropriately managed. Still, mortality is generally associated with underlying diseases (such as advanced diabetes or malignancy) rather than gastroparesis alone.

Can digestive enzymes help with gastroparesis?

Digestive enzymes have not been shown in clinical trials to be effective for improving symptoms or gastric emptying in gastroparesis, as the primary problem lies with gastric motility (muscle and nerve function) rather than breakdown of food or enzyme insufficiency.

How to detect gastroparesis?

Detection of gastroparesis primarily through tests that measure gastric emptying, often after ruling out mechanical obstructions. Gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) is the gold standard for diagnosis; however, other methods, such as breath tests and wireless motility capsules, are also used.

Can diabetic gastroparesis be reversed?

Diabetic gastroparesis is generally considered a chronic condition that is difficult to reverse. Treatments aim to manage and reduce symptoms, optimise glycaemic control, and prevent complications. Some short-term cases related to acute hyperglycaemia may show improvement with blood sugar optimisation, but most established cases are not reversible; however, careful management can decrease severity and improve the quality of life for the patient.

Can gallstones cause gastroparesis?

Gallstones are not a direct cause of gastroparesis. Gastroparesis results from impaired gastric motility and nerve dysfunction, while gallstones typically cause symptoms due to obstruction or inflammation of the biliary tract. However, gallstones may produce similar symptoms (such as abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting), so differentiation is important when evaluating patients.

Does gastroparesis cause constipation?

Gastroparesis usually affects the stomach, resulting in delayed gastric emptying. While it most commonly causes upper gastrointestinal symptoms, it can be associated with constipation, particularly if there is generalised slow gastrointestinal transit or in the context of comorbid conditions such as diabetes.

Can gastroparesis cause back pain?

Back pain is not a classic symptom of gastroparesis, which is characterized mainly by upper abdominal symptoms such as vomiting, nausea, early satiety, and bloating. However, severe bloating or abdominal distention may occasionally radiate discomfort toward the back, but this is not commonly reported in the literature as a primary symptom.

What are the home remedies for gastroparesis?

Home management of gastroparesis centers on dietary and lifestyle modifications: eating small, frequent meals; choosing low-fat and low-fiber foods; chewing food thoroughly; drinking plenty of fluids; avoiding carbonated drinks and alcohol; sitting upright after meals; and incorporating gentle post-meal physical activity such as walking. These measures may help control symptoms and maintain adequate nutrition.

What surgical options are available for treating gastroparesis?

Surgical interventions for gastroparesis are considered only after dietary management, medical therapy, and less invasive procedures have failed to control symptoms or maintain adequate nutrition. Surgery is reserved for severe, refractory cases due to its risks and variable effectiveness. Common surgical procedures include jejunostomy tube feeding, gastric electrical stimulation, and venting gastrostomy.

How does a low-fat, low-fibre diet improve gastroparesis?

A low-fat, low fibre diet improves gastroparesis by promoting better and faster gastric emptying and reducing symptoms. High-fat foods slow down stomach emptying, which can worsen gastroparesis symptoms like nausea, bloating, and fullness, so limiting fat intake helps food move more efficiently through the stomach.

Can gastroparesis cause weight gain?

Yes, gastroparesis can cause weight gain in some individuals, although it is more commonly associated with weight loss. In some cases, patients may gain weight due to reduced physical activity, increased intake of easily digestible high-calorie foods, or fluid retention from certain treatments, despite impaired gastric emptying.

Is ginger good for gastroparesis?

Yes, ginger may be helpful for some people with gastroparesis, especially for relieving mild nausea and possibly improving gastric emptying. Studies have shown that ginger can stimulate gastric motility and reduce nausea through its effects on the gut and nervous system.

When to consult a doctor for gastroparesis?

Consult a doctor for gastroparesis if there is ongoing nausea, frequent vomiting, or a feeling of fullness soon after starting a meal. Signs that indicate a need for medical assistance are:

- Unexplained weight loss or poor appetite

- Abdominal bloating or persistent discomfort

- Vomiting undigested food hours after eating

- Blood sugar levels that are difficult to control (especially in people with diabetes)

- Digestive problems that disrupt regular activity

If these symptoms continue, it is best to see a gastroparesis doctor for an accurate diagnosis and treatment. Seek emergency medical attention if you cannot keep fluids down, vomit blood, or develop severe abdominal pain, as these may signal complications. A general physician or gastroenterologist can provide the right gastroparesis treatment to manage symptoms and reduce long-term risks.

Share on

Request an appointment

Fill in the appointment form or call us instantly to book a confirmed appointment with our super specialist at 04048486868

Appointment request - health articles

Recent Articles