Psoriatic Arthritis - Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment & Prevention

PACE Hospitals

Psoriatic arthritis definition

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disease that affects both the skin and the joints. It happens when the immune system of the body unintentionally targets healthy cells, causing joint inflammation and overproduction of skin cells. This results in the combination of psoriasis (a skin condition causing red, scaly patches) and arthritis (joint pain, stiffness, and swelling). Symptoms commonly include joint pain, morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes, dactylitis (swelling of the fingers and toes), enthesitis (tenderness where tendons/ligaments attach to bone), nail changes and fatigue.

The exact cause is unknown, however, it is thought to be caused by the combination of genetic, immune, and environmental factors. Individuals with a family history of psoriasis or arthritis are at higher risk. Triggers such as infections, physical injury, or stress can exacerbate the condition. Untreated psoriatic arthritis can lead to permanent joint damage, disability, and reduced quality of life. Complications may include uveitis (eye inflammation), cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome.

A rheumatologist, a doctor specialised in autoimmune and musculoskeletal diseases, can provide an accurate diagnosis and develop an appropriate treatment plan to reduce inflammation, alleviate symptoms, and avoid joint damage.

Psoriatic arthritis meaning

The term “psoriatic arthritis” is derived from Greek words:

- “Psoriatic”: Meaning "itch" or “scaly skin disease”.

- “Arthritis”: Meaning “joint” and “-itis" meaning “inflammation”.

So, psoriatic arthritis literally means joint inflammation associated with psoriasis.

Psoriatic Arthritis Statistics

Psoriatic arthritis statistics Worldwide

The worldwide prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in the general adult population is around 112 cases per 100,000 adults. However, there is significant regional variation in these figures. Prevalence is generally higher in Europe and North America, with pooled estimates of approximately 188 and 133 cases per 100,000 adults, respectively. The prevalence appears lower in Asia (around 48 per 100,000) and South America (roughly 17 per 100,000).

Psoriatic arthritis statistics in India

In India, PsA affects approximately 8.7% of patients with psoriasis, which has a prevalence of 0.4–2.8% in the general population. Studies suggest the prevalence of PsA among Indian psoriasis patients ranges from 4.4% to 8.7%, with one large study identifying it in 8.7% of psoriasis patients in a specific region.

PsA usually follows the diagnosis of psoriasis by about 10 years. However, in 15% of cases, arthritis and psoriasis begin simultaneously, and in another 15%, arthritis may precede psoriasis by up to 15 years.

Psoriatic Arthritis Types

Psoriatic arthritis can be categorised into several patterns based on joint involvement and distribution. Based on the Moll and Wright classification of psoriatic arthritis, there are 5 types of psoriatic arthritis, each presenting with distinct clinical features and varying degrees of severity, which can aid in diagnosis and guide appropriate management strategies.

The following are the most common types of psoriatic arthritis:

- Asymmetric oligoarthritis (asymmetrical psoriatic arthritis)

- Symmetric polyarthritis (Symmetric psoriatic arthritis)

- Distal interphalangeal (DIP) predominant arthritis

- Spondylitis (axial psoriatic arthritis)

- Arthritis mutilans (severe destructive form)

Asymmetric oligoarthritis (asymmetrical psoriatic arthritis)

This is one of the most common types of PsA, affecting a few joints (fewer than five) in an asymmetrical pattern. The joint pain and swelling appear on different sides of the body, such as the left knee and a finger on the right hand. This form is often milder than symmetric polyarthritis, but some patients will see it progress to the more widespread, symmetrical form over time. It can affect both small joints in the hands and feet, as well as larger joints like the knee.

Symmetric polyarthritis (Symmetric psoriatic arthritis)

This type involves five or more joints at the same time, affecting the same joints on both sides of the body. It can sometimes resemble rheumatoid arthritis, but PsA can cause a characteristic dactylitis ("sausage-like" swelling of the fingers and toes) that is not typical of RA. It can range from mild to severe; this form of PsA can be more disabling and lead to progressive joint destruction.

Distal interphalangeal (DIP) predominant arthritis

This form mainly affects the distal interphalangeal joints, which are the small joints closest to the fingertips and toenails. It is strongly associated with nail changes seen in psoriasis, such as pitting, ridging, and onycholysis (nail separation). Because these joints are small, the pain and swelling are localised to the tips of the fingers or toes, often giving a distinctive appearance. This type of PsA is also known as distal psoriatic arthritis.

Spondylitis (axial psoriatic arthritis)

Spondylitic psoriatic arthritis mainly involves the spine and the sacroiliac joints, which connect the spine to the pelvis. People with this type suffer from back pain, stiffness, and decreased flexibility, particularly after extended periods of relaxation. The neck and chest wall joints may also be affected, making movement and breathing extremely uncomfortable. This type can occur alone or alongside other forms of psoriatic arthritis that affect the limbs.

Arthritis mutilans (severe destructive form)

Arthritis mutilans is the rarest but most severe form of psoriatic arthritis. It leads to extreme joint destruction, particularly in the small joints of the hands and feet. Over time, this may lead to bone erosion and deformities, causing fingers and toes to shorten or "telescope". Joint fusion can also occur, which results in a loss of function. Initial detection and prompt treatment are essential to prevent or slow this severe damage.

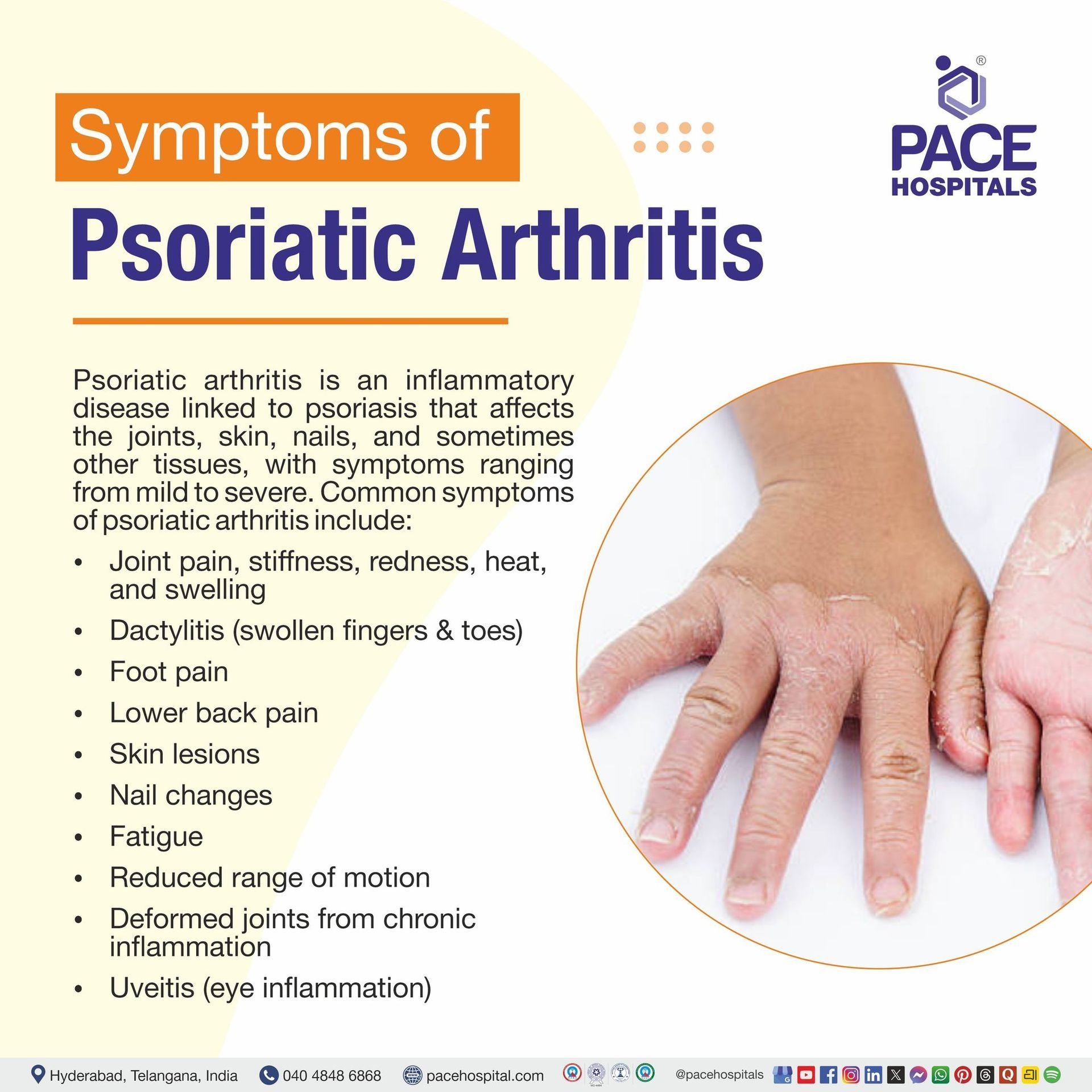

Psoriatic Arthritis Symptoms

Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory condition that often overlaps with psoriasis. It can affect joints, skin, nails, and other tissues. Its symptoms can vary widely between people and may range from mild to severe. Below are some of the common symptoms of psoriatic arthritis:

- Joint pain, stiffness, redness, heat, and swelling

- Dactylitis (Swollen fingers and toes)

- Foot pain

- Lower back pain

- Skin lesions

- Nail changes

- Fatigue

- Reduced range of motion

- Deformed joints from chronic inflammation

- Uveitis (Eye Inflammation)

Joint pain, stiffness, redness, heat, and swelling: Inflammation of the joints is the hallmark feature of psoriatic arthritis. The immune system's overactivity leads to thickening of the joint lining (synovia) and an increase in joint fluid, which causes stiffness, redness, pain, heat, and swelling. Stiffness is often most noticeable in the morning or after rest, and tends to improve with movement. Increased blood flow and inflammation may lead to the affected joints feeling warm when touched.

Dactylitis (Swollen fingers and toes): Dactylitis, also called “sausage digits,” is a distinctive clinical feature of psoriatic arthritis. It occurs when both the joints and tendons of an entire finger or toe become inflamed, leading to uniform swelling along the entire length of the digit. This happens because the inflammation extends beyond the joints to the surrounding soft tissues.

Foot pain: Psoriatic arthritis foot pain often results from enthesitis, where tendons and ligaments attach to bones. Common sites include the Achilles tendon (at the back of the heel) and plantar fascia (on the bottom of the foot). This can make walking or standing painful, especially in the morning or after prolonged activity. The soles of the feet may feel tender, and swelling around the heels or arches can develop due to persistent inflammation.

Lower back pain: Some people with psoriatic arthritis develop spondylitis, an inflammation of the spinal joints, particularly in the lower back and sacroiliac joints (where the spine meets the pelvis). This causes chronic lower back discomfort and stiffness, often after rest or at night. Moving around generally relieves the pain. In extreme cases, inflammation may cause decreased flexibility or fusion of spinal joints, limit motion and leading to long-term discomfort.

Skin lesions: Skin lesions are a classic feature of psoriasis, which frequently accompanies psoriatic arthritis. These appear as red, scaly, and often itchy patches on the skin, commonly on the scalp, elbows, knees, or back. The lesions result from an overproduction of skin cells due to immune system overactivity. The presence of these lesions helps in diagnosing psoriatic arthritis, as most people with PsA have or have had psoriasis at some point.

Nail changes: Nail involvement is another common symptom of psoriatic arthritis. Pitting (small dents), ridging, discolouration, and onycholysis (nail bed separation) are all possible symptoms. These changes arise because psoriasis can damage the nail matrix and surrounding tissues. Psoriatic arthritis nail symptoms often accompany joint inflammation, especially in the small joints near the fingertips, and can help differentiate psoriatic arthritis from other arthritic conditions.

Fatigue: Fatigue in psoriatic arthritis is caused by chronic inflammation and the body’s ongoing immune response. The immune system’s overactivity releases inflammatory chemicals called cytokines, which can lead to tiredness and low energy.

Reduced range of motion: Inflammation within the joints causes stiffness and swelling, which limit movement. Over time, chronic inflammation can lead to joint damage, thickening of surrounding tissues, and formation of scar tissue, all of which reduce flexibility.

Deformed joints from chronic inflammation: In advanced or poorly controlled psoriatic arthritis, long-term inflammation can lead to joint deformities. The destruction of cartilage and bone, along with changes in the alignment of joints, can cause fingers or toes to appear shortened, crooked, or fused. This is most severe in a form called arthritis mutilans, where the bones collapse, leading to a “telescoping” appearance of the digits.

Uveitis (Eye Inflammation): Uveitis, an inflammation of the middle layer of the eye, can occasionally result in pain, redness, and blurred vision. In order to avoid complications, it is important to treat it right away.

Psoriatic Arthritis Causes

The cause of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is not fully understood; it is an autoimmune disease resulting from a mix of genetic, immunological, and environmental factors. In people with PsA, the immune system mistakenly attacks normal cells and tissue, causing the inflammation that leads to joint and skin symptoms.

The common causes of psoriatic arthritis are:

- Genetic factors

- Immune system dysfunction

- Environmental triggers

- Abnormal immune response to skin disease (psoriasis)

Genetic factors: Genetic factors play a major role in the development of psoriatic arthritis. Research shows that PsA often runs in families — many patients have a parent or sibling with psoriasis or arthritis. Certain genes, particularly HLA-B27, HLA-Cw6, HLA-B38, and HLA-B39, have been linked to an increased risk of developing PsA. These genes control how the immune system recognises and reacts to its own tissues. Certain gene variants can lead the immune system to mistakenly see healthy joint and skin cells as foreign, causing inflammation.

Immune system dysfunction: Genetic factors play a central role in the development of psoriatic arthritis. Usually, it protects the body from infections. However, in PsA, the immune system becomes overactive and attacks healthy tissues. This leads to chronic inflammation in the joints, tendons, and skin. The immune cells release inflammatory chemicals (cytokines), such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins (IL-17, IL-23), which cause swelling, pain, and tissue damage. This ongoing immune response drives both the psoriatic skin lesions and the joint inflammation of PsA.

Environmental triggers: Environmental factors can trigger psoriatic arthritis in people who are genetically predisposed. Infections, such as strep throat or viral diseases, can activate the immune system and lead to inflammation. Physical trauma or injury to the skin or joints (known as the Koebner phenomenon) may also trigger symptoms in some individuals.

Abnormal immune response to skin disease (psoriasis): In most cases, psoriatic arthritis develops in people who already have psoriasis, a chronic skin condition. The same immune system malfunction that causes psoriasis can extend beyond the skin to affect the joints. In psoriasis, the immune system mistakenly speeds-up the growth cycle of skin cells, leading to red, scaly patches. Over time, this abnormal immune activity may spread systemically, attacking the tissues in and around the joints, resulting in joint inflammation and pain.

Psoriatic Arthritis Risk Factors

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) develops through a combination of individual traits and environmental influences. The risk factors listed below are not definite, but they are associated with a higher likelihood of developing PsA in people, especially those with psoriasis or a family history of the condition. The risk factors are:

- Age

- Gender

- Existing psoriasis

- Infections

- Being obese

- Physical trauma

- Stress and lifestyle factors

- Smoking

- Family history

Age: PsA can occur at any age, but most commonly develops between ages 30 and 50, often after the onset of psoriasis. This may be due to prolonged immune activity, environmental exposures, hormonal changes, and accumulated immune system stress during middle age, increasing susceptibility to autoimmune inflammation.

Gender: Both men and women can develop psoriatic arthritis, but certain patterns differ by gender. Studies suggest that men are slightly more prone to the spondylitic (spinal) form of PsA, whereas women may experience more peripheral joint involvement and enthesitis (inflammation where tendons attach to bones).

Existing psoriasis (psoriasis severity and skin involvement): Having psoriasis is the strongest known risk factor for PsA. More extensive or severe skin disease, including nail involvement or scalp lesions, is associated with a higher chance of developing joint and entheseal inflammation. This reflects shared inflammatory pathways in the skin and joints and how active skin disease can signal systemic inflammatory activity.

Infections: Certain infections, particularly bacterial infections like streptococcal throat infections, can trigger or worsen psoriatic arthritis in genetically predisposed individuals. These infections activate the immune system, which in some cases mistakenly targets the body’s own tissues, including joints and skin.

Being obese: Obesity is consistently identified as a modifiable risk factor for both psoriasis and PsA. Excess body fat increases the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukins, which contribute to systemic inflammation and autoimmune activation. Additionally, carrying excess weight puts extra stress on the joints, worsening pain and stiffness.

Physical trauma: Skin or joint injuries can precipitate a psoriatic arthritis flare-up or, in susceptible individuals, contribute to the development of arthritis at those sites. This Koebner phenomenon reflects how local tissue injury can trigger immune responses that manifest as skin or joint inflammation.

Stress and lifestyle factors: Chronic stress and certain lifestyle factors can modulate immune function and inflammation. While not causal on their own, stress can influence disease activity and may interact with other risk factors to promote PsA onset or worsen progression.

Smoking: Smoking has been shown to increase the risk and severity of psoriatic arthritis. It promotes inflammation, weakens immune system regulation, and lowers the body’s ability to respond effectively to treatment. Smoking can also increase oxidative stress and impair blood flow, which can worsen both skin and joint symptoms.

Family history: A family history of psoriasis or PsA can raise the risk of developing the condition. This is because specific genetic markers are inherited and influence how the immune system functions. People who have a close relative (parent, sibling, or child) with psoriasis or PsA have a much higher likelihood of developing the disease themselves.

Psoriatic Arthritis Complications

Psoriatic arthritis can cause severe complications, particularly when left untreated. The chronic systemic inflammation associated with PsA can damage multiple organs and lead to life-altering health conditions in addition to joint and skin issues. The following are the complications of PsA:

- Persistent inflammatory disease

- Uveitis

- Metabolic syndrome

- Cardiovascular diseases

Persistent inflammatory disease: PsA is a chronic inflammatory disease that, if unmanaged, can cause lasting joint damage, pain, stiffness, and loss of mobility. Prolonged inflammation may also affect other organs, including the heart, eyes, and blood vessels, leading to serious complications and disability.

Uveitis: Uveitis is a common eye-related complication of psoriatic arthritis, caused by inflammation of the uvea. It causes red, painful eyes, light sensitivity, blurred vision, and can threaten vision if not treated. Shared inflammatory pathways between skin, joints, and the eye explain why eye involvement can accompany PsA.

Metabolic syndrome: Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions, including high blood pressure (hypertension), obesity, high blood sugar, and abnormal cholesterol levels, that often occur alongside psoriatic arthritis. Chronic inflammation from PsA disrupts the body’s normal metabolism, promoting insulin resistance and fat accumulation. In addition, some medications used to manage PsA can influence lipid or glucose levels. Together, these factors increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, making metabolic syndrome a serious systemic complication.

Cardiovascular diseases: People with PsA are at a significantly higher risk of developing heart disease, including hypertension (high blood pressure), high cholesterol, atherosclerosis,

heart attack, and

stroke. Chronic inflammation strains the heart and damages blood vessels.

Psoriatic Arthritis Diagnosis

Diagnosing PsA can be challenging because its symptoms often overlap with other forms of arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. There is no single test that can confirm PsA, so diagnosis relies on a combination of medical history, physical examination, imaging studies, and laboratory tests. Early and accurate diagnosis is important to prevent joint damage and long-term complications.

The following are the commonly used diagnostic steps and criteria for psoriatic arthritis:

- Clinical assessment and patient medical history

- Physical examination

- Laboratory tests

- Rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies

- Inflammatory markers- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Synovial fluid analysis

- Uric acid levels

- Antinuclear antibodies (ANA)

- Genetic testing

- Imaging test

- Plain X-rays

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSUS)

- Applying CASPAR criteria for psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic Arthritis Treatment

Treatment for psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a lifelong process that is guided by the severity of the disease and the specific body parts affected, such as the joints, spine, and skin. The approach is generally "step-up," beginning with non-pharmacological methods and moving to medication and, in rare cases, surgery if symptoms progress. They include the following:

Non-pharmacological treatment for psoriatic arthritis

- Physical exercise

- Weight management

- Heat and cold therapy

- Physical and occupational therapy

- Smoking cessation

Pharmacological treatment for psoriatic arthritis

- For mild psoriatic arthritis:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Low-dose corticosteroids

- For mild to moderate psoriatic arthritis or when NSAIDS are insufficient:

- Conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARDs)

- For moderate to severe psoriatic arthritis or when csDMARDs fail:

- Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs)

- Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors

- Interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors

- IL-12/23 inhibitors

- T-cell co-stimulation modulator

- Targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs)

- Janus kinase (JAK inhibitor)

- Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor

Surgical interventions

- Joint replacement surgery (arthroplasty)

- Synovectomy

- Joint fusion (arthrodesis)

Why Choose PACE Hospitals?

Expert Super Specialist Doctors

Advanced Diagnostics & Treatment

Affordable & Transparent Care

24x7 Emergency & ICU Support

Psoriatic Arthritis Prevention

Although psoriatic arthritis (PsA) cannot always be completely prevented, early lifestyle and medical measures can significantly reduce its risk or delay its onset, especially in individuals with psoriasis. The following are the preventive tips:

- Maintaining a healthy weight

- Ensuring regular exercise

- Avoiding alcohol

- Managing stress

- Treating psoriasis effectively

- Early awareness and monitoring

Maintaining a healthy weight: Maintaining a healthy body mass index (BMI) helps reduce the overall risk of psoriatic arthritis. Obesity is a strong, modifiable risk factor because excess body fat releases inflammatory chemicals that can worsen immune activity already heightened by psoriasis. Extra weight also increases mechanical stress on joints and tendons, leading to micro-injuries that can trigger inflammation in genetically susceptible individuals.

Ensuring regular exercise: Regular physical activity promotes anti-inflammatory effects throughout the body. Moderate exercise helps regulate immune responses, improve blood circulation, and strengthen muscles that support the joints. It also prevents obesity, improves insulin sensitivity, and lowers stress levels, all of which indirectly protect against inflammatory joint disease.

Avoiding alcohol: Avoiding or limiting alcohol can help prevent psoriatic arthritis by minimising immune and liver stress. Excessive alcohol intake increases inflammatory cytokines and can worsen psoriasis severity. Alcohol also interferes with metabolism and immune balance, creating an environment that may promote autoimmune reactions.

Managing stress: Stress is a trigger for psoriasis flares and may also influence the onset of psoriatic arthritis. Chronic psychological stress activates the body’s stress hormones and immune pathways that release pro-inflammatory molecules. Over time, this can increase systemic inflammation and promote autoimmune responses. Effective stress-management techniques such as mindfulness, yoga, deep breathing, or counselling can lower inflammatory markers, stabilise immune function, and help prevent psoriasis from progressing to joint disease.

Treating psoriasis effectively: Proper and timely treatment of psoriasis plays a key role in preventing psoriatic arthritis. Studies show that controlling skin inflammation with systemic or biologic therapies can reduce the risk of developing arthritis. Effective psoriasis management prevents continuous immune activation in the skin that could otherwise spread into joints and entheses.

Early awareness and monitoring: Regularly checking for early signs such as joint pain, stiffness, swelling, or nail changes helps detect psoriatic arthritis early and prevent joint damage. Recognising personal risk factors like family history, severe psoriasis, nail involvement, obesity, smoking, or joint injury allows for timely lifestyle and medical interventions. Together, early monitoring and risk awareness help reduce inflammation and delay PsA progression.

Difference between Rheumatoid arthritis and Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis vs rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriatic arthritis are both chronic inflammatory joint diseases, but differ in their underlying causes, clinical presentation, and associated features. Understanding the differences between the diseases is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. The following key distinctions between psoriatic arthritis and RA help clarify their unique characteristics.

| Parameters | Psoriatic arthritis | Rheumatoid arthritis |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | This is a chronic inflammatory arthritis associated with psoriasis, where the immune system causes inflammation in joints, tendons, and surrounding tissues. | This is a chronic autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks the synovial membrane of joints, causing inflammation, pain, swelling, and progressive joint destruction. |

| Cause | Inflammatory arthritis associated with psoriasis (skin and nail disease) | Autoimmune disease primarily targets the synovial membrane. |

| Onset | It can occur at any age, often in people with existing psoriasis. | Usually gradual; more common in middle-aged women |

| Joint involvement | Often asymmetric, but can become symmetric later | Symmetric joint involvement |

| Skin lesions | Present as psoriasis (scaly, red skin patches) | Absent |

| Rheumatoid factor (RF) / Anti-CCP antibodies | Usually negative (seronegative arthritis) | Usually, positive |

| Response to treatment | Treated with DMARDs and biologics targeting TNF, IL-17, or IL-23 | Responds to DMARDs and biologics targeting TNF and IL-6 |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA)

What are the first signs of psoriatic arthritis?

The earliest signs are often mild and intermittent. These include joint pain, swelling, stiffness (especially in hands, feet, wrists), and fatigue. Sometimes, small patches of psoriasis or nail changes (tiny pits, ridges, or nail separation) appear first or concurrently.

What is the treatment for psoriatic arthritis?

Treatment aims to relieve pain, reduce inflammation, prevent joint damage, and improve quality of life. Common therapies include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), low-dose steroids, conventional disease-modifying drugs, and biologic or targeted drugs (e.g. TNF inhibitors, IL-17/IL-23 inhibitors, JAK inhibitors). Physical therapy, lifestyle changes, and skin treatments are also part of comprehensive care.

How to test for psoriatic arthritis?

Testing for psoriatic arthritis combines medical history, physical exam, and tests such as blood work and imaging. Blood tests rule out other conditions and check inflammation, while imaging (X-ray, ultrasound, MRI) looks for joint or spine changes typical of PsA. A dermatologist or rheumatologist evaluates skin psoriasis alongside joint symptoms to ensure the correct diagnosis.

How long does a psoriatic arthritis flare last?

The duration of a psoriatic arthritis flare is variable. On average, flares last about 16 days in many people. Yet, some flares may last only a few days, and others extend for several weeks, depending on how active the inflammation is, how well treatment works, and individual factors.

Is psoriatic arthritis life-threatening?

PsA itself is usually not life-threatening, but it can cause serious problems if not treated, such as joint damage, reduced function, and reduced quality of life. Rarely, severe inflammation can affect organs or lead to systemic problems. Modern treatments aim to control inflammation and prevent damage. Regular follow-up, adherence to therapy, and monitoring for side effects are important for long-term outcomes.

How to avoid psoriatic arthritis?

Maintaining a healthy weight, regular gentle exercise, and avoiding smoking may lower inflammation and reduce flare-ups in people with psoriasis, which can lower the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Manage skin symptoms promptly, control stress, and get regular follow-ups with a clinician to monitor joints if psoriasis is present. While these steps can help, there is no guaranteed way to prevent PsA entirely, as genetics also play a role.

Is psoriatic arthritis a form of rheumatoid arthritis?

No. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are distinct diseases. PsA is a different type of inflammatory arthritis linked to psoriasis, and while they share some features, they differ in cause, joint patterns, and lab tests.

Can psoriatic arthritis cause a high white blood cell count (WBC)?

Yes, PsA can cause a mild to moderate increase in WBC due to chronic systemic inflammation. This type of elevation, called reactive leukocytosis, is common in inflammatory diseases. However, high WBC counts may indicate other conditions such as infection, medication side effects, or hematologic disorders, and should be further investigated.

How does psoriatic arthritis progress?

The course is variable between individuals. Many people start with skin symptoms (psoriasis), and arthritis appears years later. Over time, if untreated, inflammation can damage bone, cartilage, and joints, leading to stiffness, deformity, loss of function, and in rare cases severe bone loss (arthritis mutilans).

Which biologic is best for psoriatic arthritis

The best biologic for psoriatic arthritis depends on individual factors like disease pattern, skin involvement, other health conditions, and previous treatments. Common options target immune pathways involved in PsA and can include TNF inhibitors or agents targeting IL-17 or IL-12/23.

Can psoriatic arthritis affect the eyes?

Yes. Psoriatic arthritis can involve the eyes, most often as uveitis (inflammation inside the eye) or dry eye. Psoriatic arthritis eye symptoms may include eye redness, pain, light sensitivity, blurry vision, or a gritty sensation. Eye involvement is more common in people with active skin or joint disease.

What does psoriatic arthritis look like?

PsA can look different from person to person. Common features include swollen fingers or toes (sausage digits), joint pain and morning stiffness, back pain, and skin or nail psoriasis. Some people have only joint symptoms without skin changes. The condition may flare with skin psoriasis outbreaks.

What are the neurological complications of PsA?

Neurological complications in psoriatic arthritis can occur, but are not the main feature of the disease. Possible issues include neuropathic pain (tingling or burning nerves), headaches or migraines, dizziness, and occasionally cognitive or mood changes. Rarely, inflammation or treatment side effects may be linked to seizures or stroke.

When to consult a doctor for psoriatic arthritis?

Consult a doctor for psoriatic arthritis if you experience joint pain, stiffness, or swelling, especially when you already have psoriasis or a family history of it. Warning signs that require medical attention include:

- Chronic joint pain, tenderness, or morning stiffness lasting more than a few weeks

- Swelling in fingers or toes (“sausage-like” appearance)

- Changes in nails, such as pitting, thickening, or separation from the nail bed

- Fatigue or difficulty performing daily activities due to joint pain

- Back or heel pain that worsens with rest

If these symptoms continue, it is best to see a psoriatic arthritis doctor for an accurate diagnosis and treatment. Seek emergency medical attention if you develop severe pain, sudden joint swelling, or vision problems, as these may indicate complications. A rheumatologist can provide the right psoriatic arthritis treatment to manage symptoms and reduce long-term risks.

Share on

Request an appointment

Fill in the appointment form or call us instantly to book a confirmed appointment with our super specialist at 04048486868

Appointment request - health articles

Recent Articles