Achalasia Cardia - Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment

PACE Hospitals

Written by: Editorial Team

Medically reviewed by: Dr. Govind Verma - Senior Consultant Gastroenterologist & Hepatologist

Overview | Prevalence | Types | Symptoms | Causes | Risk Factors | Complications | Diagnosis | Treatment | Prevention | Achalasia Cardia vs GERD | FAQs | When to consult a Doctor

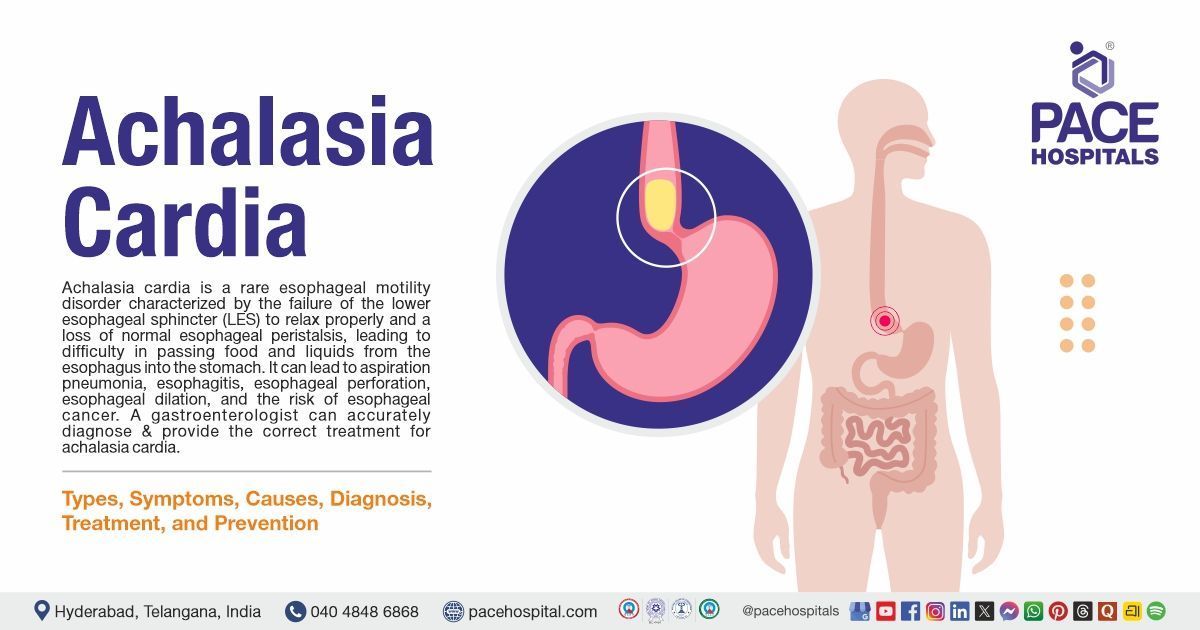

Achalasia cardia definition

Achalasia cardia is a rare esophageal motility disorder characterized by the failure of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to relax properly and a loss of normal esophageal peristalsis, leading to difficulty in passing food and liquids from the esophagus into the stomach.

Symptoms include difficulty swallowing solids and liquids, regurgitation of undigested food or saliva, chest pain, heartburn, night-time coughing, and weight loss. If untreated, complications such as aspiration pneumonia, esophagitis, esophageal perforation, esophageal dilation, recurrence, and an increased risk of esophageal cancer may occur.

There's no cure for achalasia cardia. Once the esophagus is paralyzed, the muscle cannot work properly again. But symptoms can usually be managed with endoscopy, minimally invasive therapy, or surgery.

A gastroenterologist (a specialist in digestive system disorders) can successfully diagnose, treat, and manage the problem, ensuring proper healing and preventing complications.

Achalasia cardia meaning

The term "achalasia cardia" is derived from the Greek words:

- “Achalasia” means failure to relax

- “Cardia” refers to the lower end of the esophagus, where it meets the stomach (also known as the lower esophageal sphincter, or LES.

Achalasia Cardia Prevalence

Achalasia cardia prevalence Worldwide

Achalasia cardia is a rare esophageal motility disease with a worldwide prevalence estimated at approximately 10 to 40 cases per 100,000 people. The global pooled incidence and prevalence of achalasia were estimated to be 0.78 cases per 100,000 person-years, affecting both males and females equally. It is most commonly diagnosed between the ages of 25 and 60, although it can occur at any age. The condition is rare in children. While achalasia occurs globally without a strong geographical pattern, some studies suggest a slightly higher incidence in certain regions, such as South America and parts of Northern Europe.

Achalasia cardia prevalence in India

Achalasia cardia is an esophageal motility condition with an estimated frequency of 0.5 to 1.0 per 100,000 people per year. This condition is rare and affects about 10 in 100,000 individuals. It most frequently happens between the ages of 30 and 60. The occurrence in the paediatric population is very low and is even rarer in infants.

Achalasia Cardia Types

Achalasia cardia is a heterogeneous esophageal motility disorder categorized into three distinct types based on manometric patterns of the esophagus (i.e., pressure and movement measurements of esophageal contractions during swallowing), as defined by the Chicago Classification. This widely accepted system classifies achalasia into:

- Type I: It is also called classic achalasia. The oesophagus doesn’t move food down well in this condition, but shows minimal contractility (very little activity).

- Type II: In this type, pressure builds up in the esophagus, causing it to become compressed with intermittent periods of panesophageal pressurization, where the entire esophagus exerts pressure to push food down, but this doesn’t happen consistently.

- Type III: It is also known as spastic achalasia because it involves premature or spastic contractions in the lower part (bottom) of the oesophagus, where it meets the stomach, which is the most severe type of achalasia. The contractions may cause chest pain that can wake a person from sleep and mimic the symptoms of a heart attack.

Achalasia Cardia Symptoms

Achalasia occurs gradually and is mostly caused by the failure of the LES to relax and loss of esophageal peristalsis. Achalasia cardia signs and symptoms include the following:

- Backflow (regurgitation) of food

- Chest pain

- Cough

- Heartburn

- Weight loss

- Choking

- Dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing)

- Hiccups or difficulty belching

Backflow (regurgitation) of food: In achalasia, food and liquids cannot pass easily into the stomach because the LES fails to relax and the esophageal muscles lose their coordinated contractions. This causes swallowed material to collect in the esophagus. Over time, the retained food can flow backward into the mouth, especially when lying down, leading to regurgitation without nausea or retching.

Chest pain: The esophagus can become distended, and its muscles may spasm as it tries unsuccessfully to push food through the tightly closed LES. This creates pressure and discomfort in the chest, often mistaken for heart-related pain. The pain may be burning or sharp and can occur during swallowing or even at rest.

Cough: When regurgitated food or liquid enters the throat, small amounts may accidentally enter the airway (aspiration), triggering a cough reflex. This is particularly common at night when lying down, as gravity makes it easier for the retained material in the esophagus to move upward and toward the windpipe.

Heartburn: Although achalasia is not caused by excess stomach acid, the fermentation of retained food in the esophagus produces acidic substances that irritate the lining. Additionally, the pressure build-up in the esophagus can resemble the burning sensation of heartburn, leading to misdiagnosis as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Weight loss: Because swallowing is difficult and often uncomfortable, people with achalasia may avoid eating or reduce their food intake. Combined with inefficient nutrient absorption from prolonged esophageal stasis, this leads to gradual, unintended weight loss.

Choking: Regurgitated food or saliva can suddenly enter the throat while eating or sleeping. If the airway is partly blocked by this material, it can lead to choking episodes, which may be frightening and potentially dangerous if severe aspiration occurs.

Dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing): Dysphagia is the hallmark symptom of achalasia. It occurs because the LES remains tightly contracted and the esophageal muscles fail to generate effective peristaltic waves. Patients often report difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids from the early stages of the disease.

Hiccups or difficulty belching: The LES in achalasia is abnormally tight and unresponsive, which not only prevents food from passing into the stomach but also traps swallowed air. This makes it hard to belch. It can also cause hiccups as the body tries to release the trapped gas with sudden diaphragm contractions.

Achalasia Cardia Causes

Although the exact etiology remains unclear in many cases, both primary (idiopathic) and secondary (acquired) causes have been proposed. Understanding the underlying mechanisms contributing to the development of achalasia is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

The etiology of achalasia cardia is generally classified into two main types:

- Primary (idiopathic) achalasia

- Secondary achalasia

Primary (Idiopathic) Achalasia

- This is the most common form and results from degeneration of nerve cells in the esophageal myenteric plexus, including inhibitory neurons that produce nitric oxide (NO) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), which are essential for LES relaxation and normal esophageal motility.

- The cause of this neuronal degeneration is unknown but likely involves autoimmune mechanisms, viral infections (such as herpes simplex, varicella-zoster, measles viruses), genetic predisposition (including certain HLA associations), and possibly environmental factors. Primary achalasia is termed idiopathic because no specific cause is identified.

Secondary Achalasia (Pseudoachalasia)

Secondary achalasia resembles primary achalasia symptoms but is caused by other underlying conditions, including:

- Infectious diseases such as Chagas disease, caused by Trypanosoma cruzi infection, which damages enteric nerves.

- Malignant tumors infiltrating the esophagus or gastroesophageal junction (gastric cardia carcinoma, lymphoma, or metastases).

- Less common causes include eosinophilic gastroenteritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and multiple system atrophy.

- Post-surgical states or other systemic diseases may also cause secondary achalasia.

Achalasia Cardia Risk Factors

Achalasia cardia is a rare esophageal motility condition in which the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) fails to relax properly and the esophageal muscles lose coordinated contractions. The recognized risk factors include:

- Genetic factors

- Gender

- Autoimmune mechanisms

- Viral infections

- Socioeconomic and lifestyle factors

- Other factors

Genetic factors: Certain inherited characteristics or genetic syndromes, such as Allgrove syndrome or Down syndrome, enhance the risk of developing achalasia. These diseases are frequently associated with the autonomic nervous system, which affects the development or survival of nerve cells in the esophagus. When these nerve cells, particularly those that produce inhibitory signals for the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), are reduced or dysfunctional, the LES fails to relax properly. Over time, this leads to impaired passage of food and the characteristic symptoms of achalasia.

Gender: Achalasia affects men and women approximately equally. Although some differences in esophageal motility between genders exist, clinical differences in achalasia by gender are limited and inconsistent due to disease rarity.

Autoimmune mechanisms: In autoimmune diseases like scleroderma and Addison’s disease, the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues. In achalasia, this immune response affects the nerve cells in the esophageal wall, particularly those that produce nitric oxide. Nitric oxide is vital for the relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The damage to these neurons stops the LES from opening correctly when swallowing. This persistent dysfunction causes food to accumulate in the esophagus and leads to the chronic symptoms of achalasia.

Viral infections: Certain viral infections, such as varicella zoster or human papillomavirus (HPV), can increase the risk of achalasia. These viruses can either infect and harm the nerve cells of the esophagus directly or cause the immune system to attack them through a process called molecular mimicry. As these important neurons die, the LES stays tightly closed. This leads to the swallowing difficulties and regurgitation that are characteristic of the condition.

Socioeconomic and lifestyle factors

People from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and those with frequent exposure to animals through pet ownership have been found to have a higher risk of achalasia. Lower socioeconomic status may be associated with increased exposure to diseases, environmental pollutants, and poor nutrition, all of which can impair nerve function.

Close contact with animals could expose individuals to infectious agents that, in some cases, might initiate immune responses against esophageal neurons. These factors, acting over time, can contribute to the degeneration of the nerves controlling the LES.

Other Factors

Certain medical conditions and treatments can secondarily cause achalasia. Spinal cord injuries can interrupt nerve signals to the LES, Chagas disease (Trypanosoma cruzi infection) can directly destroy esophageal nerve cells, and repeated endoscopic sclerotherapy for variceal bleeding can damage the myenteric plexus.

Eating disorders like anorexia nervosa, through severe malnutrition, can also weaken nerve health. In each case, the final effect is the same: loss or dysfunction of the nerve cells that allow the LES to relax, producing symptoms of achalasia.

Achalasia Cardia Complications

The problems of achalasia cardia mainly come from long-term poor movement in the esophagus and food getting stuck. The main complications include:

- Esophageal perforation

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Esophageal cancer

- Recurrence

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Bloating

- Potential cancer risk

Esophageal perforation: The chronically dilated and weaker esophageal wall in advanced achalasia is more vulnerable. During swallowing, increased intraluminal pressure or endoscopic/surgical procedures (like pneumatic dilation or myotomy) can tear the wall. This creates an opening between the esophagus and surrounding tissues, allowing leakage of food, saliva, and bacteria into the mediastinum, a life-threatening emergency.

Aspiration pneumonia: Because achalasia causes food and fluid to stagnate in the esophagus, these materials can regurgitate into the throat, especially when lying down. Small amounts may accidentally enter the airway (aspiration), introducing bacteria into the lungs and causing pneumonia. Chronic aspiration can also lead to recurrent lung infections and long-term respiratory damage.

Esophageal cancer: Long-standing achalasia significantly increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma, and to a lesser extent, adenocarcinoma. The constant stasis of food and saliva causes bacterial fermentation, chronic inflammation, and repeated injury to the esophageal lining. Over years, this environment promotes DNA mutations in the epithelial cells, which can eventually lead to cancer development.

Recurrence: Even after treatment, such as pneumatic dilation or Heller myotomy, symptoms may reappear. This can occur if the LES remains excessively tight, the esophagus is severely damaged from long-term disease, or scar tissue builds up. Recurrence might lead to new swallowing difficulties and regurgitation, requiring further intervention.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): Treatments for achalasia, especially surgical myotomy, weaken or cut the LES muscle to allow easier passage of food. This can also reduce its ability to prevent gastric acid from flowing back into the esophagus, leading to GERD. Acid reflux causes burning chest pain, inflammation, and may increase the risk of Barrett’s esophagus in some patients.

Bloating: In normal digestion, swallowed air can be released by belching. In achalasia, the LES dysfunction and sometimes treatment-related changes can trap air in the stomach or esophagus. This results in bloating, discomfort, and a sensation of fullness, which can be particularly bothersome after eating.

Potential cancer risk: Aside from the direct association with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, achalasia’s chronic inflammatory environment may theoretically contribute to other upper gastrointestinal malignancies over time. Persistent irritation, bacterial byproducts, and impaired mucosal defences create a precancerous state in the affected tissue. This is why patients with long-standing achalasia are often monitored with periodic endoscopy.

Achalasia Cardia Diagnosis

Achalasia Cardia can be overlooked or misdiagnosed because it has symptoms similar to other digestive disorders. To test for achalasia cardia, we recommend:

- Medical history

- Physical examination

- Imaging studies and instrumental evaluation

- Barium swallow: Patient swallows a barium contrast liquid, and X-rays show a classic “bird’s beak” narrowing at the lower esophageal sphincter with dilated esophagus above, indicating outflow obstruction.

- Upper endoscopy (EGD): A Gastroenterologist inserts a thin, flexible tube equipped with a light and camera (endoscope) down the throat to examine the inside of the esophagus and stomach. Endoscopy can be used to define a partial blockage of the esophagus if symptoms or results of a barium study indicate that possibility. Endoscopy can also be used to collect a sample of tissue (biopsy) to be tested for complications of reflux such as Barrett's esophagus.

- Esophageal manometry: This test measures the rhythmic muscle contractions in the esophagus during swallowing, the coordination and force exerted by the esophagus muscles, and how effectively the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes or opens during a swallow. This test is the most helpful when determining which type of motility problem is present.

- X-rays of the upper digestive system (esophagram): X-rays are taken after ingestion of a chalky liquid that coats and fills the lining of the digestive tract. The coating allows the doctor to see a silhouette of the esophagus, stomach, and upper intestine. A barium pill may also be given to help reveal any blockage in the esophagus.

- 24-hour pH monitoring: Measures acid exposure in the esophagus. In achalasia, acid reflux is typically absent; this test helps differentiate achalasia from GERD when symptoms overlap.

- Functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP): This tool is used to assess the geometry and distensibility of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) and esophagus, which is particularly useful in achalasia cardia evaluation.

- Endoscopic ultrasound: Uses an

ultrasoundprobe on the endoscope to visualize the esophageal wall and surrounding structures, ruling out tumors or external compression that could mimic achalasia (pseudoachalasia).

Achalasia Cardia Treatment

Achalasia cardia treatment focuses on relaxing or stretching the lower esophageal sphincter so that food and liquid can move more easily through the digestive tract.

Specific treatment depends on age, health condition, and the severity of the achalasia.

- Non-pharmacological therapy

- Dietary modifications

- Postural measures

- Lifestyle adjustments

- Regular follow-ups

- Pharmacological therapy

- Calcium channel blockers

- Nitrates

- Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

- Endoscopic botulinum toxin injection

- Surgical options for treating achalasia cardia

- Laparoscopic Heller myotomy: The surgeon cuts the muscle at the lower end of the esophageal sphincter to allow food to pass more easily into the stomach. The procedure can be done non-invasively (Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy). Some people who have a Heller myotomy may later develop gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

- Fundoplication: To avoid future problems with GERD, this procedure might be performed at the same time as a Heller myotomy. In fundoplication, the surgeon wraps the top of the stomach around the lower esophagus to create an anti-reflux valve, preventing acid from coming back (GERD) into the esophagus. Fundoplication is usually done with a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure.

- Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM): In the POEM procedure, the Gastroenterologists use an endoscope inserted through the mouth and down the throat to create an incision in the inside lining of the esophagus. Then, as in a Heller myotomy, the surgeon cuts the muscle at the lower end of the esophageal sphincter. POEM is performed after confirming the diagnosis through esophageal manometry, which remains the investigation of choice for achalasia cardia. POEM for achalasia cardia may also be combined with or followed by later fundoplication to help prevent GERD. Some patients who have a POEM and develop GERD after the procedure are treated with daily oral medication.

- Dilation of the esophageal sphincter (pneumatic dilation): A particular balloon is placed into the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) via an endoscope. The balloon is subsequently inflated at high pressure to stretch and partially rupture the LES muscle fibres. This reduces tightness at the gastroesophageal junction, allowing food and liquids to move more readily into the stomach.

- Achalasia surgery - esophageal myotomy: In this procedure, the surgeon cuts through the thickened muscle fibres of the LES (without removing any tissue). This permanently weakens the sphincter’s ability to stay tightly closed, eliminating the outflow obstruction. The cut muscle allows the esophagus to empty more freely into the stomach, relieving swallowing difficulties and reducing regurgitation.

Why Choose PACE Hospitals?

Expert Super Specialist Doctors

Advanced Diagnostics & Treatment

Affordable & Transparent Care

24x7 Emergency & ICU Support

Achalasia Cardia Prevention

Achalasia cardia cannot really be prevented because it’s caused by progressive degeneration of the nerve plexus in the esophagus (Auerbach’s plexus), and the exact reason for this degeneration is still unknown.

Preventive steps are:

- Avoiding viral infections

- Managing autoimmune diseases early

- Ensuring environmental factors

- Surveillance for longstanding disease

- Keeping general esophageal health

Avoiding viral infections: Although the exact cause of achalasia remains unclear, some studies suggests that viral infections such as measles, varicella-zoster, or herpes viruses may trigger immune-mediated injury to the myenteric plexus in genetically susceptible individuals. Preventing these infections through proper vaccination, maintaining good hygiene, and seeking early medical care when viral illnesses occur may reduce the risk of nerve damage that could potentially lead to esophageal motility disorders.

Managing autoimmune diseases early: Autoimmune mechanisms are suspected in the development of achalasia, where the body’s immune system attacks inhibitory neurons in the esophagus. Identifying and managing autoimmune conditions at an early stage can help limit the extent of nerve injury. Timely treatment with appropriate immunomodulatory therapies may reduce inflammatory damage and preserve normal swallowing function.

Ensuring environmental factors: It is suggested to avoid long-term exposure to harmful chemicals, toxins, and irritants that may impact the nervous system.

Surveillance for longstanding disease: In people who already have achalasia, prevention is centred on avoiding complications rather than the condition itself. Regular clinical evaluations, endoscopic examinations, and imaging tests allow for the early detection of growing esophageal dilatation, stasis, and precancerous changes.

Keeping general esophageal health: To promote general esophageal health, it is advised to consume a balanced diet rich in fibre, avoid very hot, very cold, or irritating meals, and treat reflux symptoms as soon as they occur. Adequate chewing, eating slowly, and drinking water with meals can all help to relieve esophageal tension. While these measures cannot ensure achalasia prevention, they do help to maintain the anatomical and functional integrity of the swallowing mechanism.

Differences between Achalasia Cardia and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Achalasia cardia and GERD are two distinct disorders affecting the esophagus, but they differ significantly in their underlying mechanisms, symptoms, and management.

The main differences between achalasia cardia and GERD are as follows:

Achalasia Cardia vs GERD

| Parameters | Achalasia cardia | Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A rare disorder in which the nerve cells in the esophagus are damaged, causing the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to remain tightly closed and preventing food from passing into the stomach. | A common condition occurs when the LES is weak or relaxes inappropriately, allowing stomach acid and contents to flow backward (reflux) into the esophagus, which can be irritating. |

| Cause | Nerve damage in the esophagus prevents LES relaxation, blocking food entry into the stomach. | A weak or overly relaxed LES allows acid and stomach contents to reflux upward. |

| Main problem | Food stasis and blockage at the LES. | Acid irritation of the esophageal lining. |

| Symptoms | Difficulty swallowing solids and liquids, regurgitation of undigested food, chest pain, and weight loss. | Heartburn, sour taste in mouth, acid regurgitation, and sometimes difficulty swallowing solids. |

| Diagnosis | Gold standard: Esophageal manometry; also barium swallow (“bird’s beak”) and endoscopy to exclude cancer. | Gold standard: 24-hour pH monitoring; also, endoscopy for mucosal injury or Barrett’s esophagus. |

| Treatment | LES pressure reduction via balloon dilation, surgical myotomy, or POEM. | Acid suppression with PPIs/H2 blockers, lifestyle changes, anti-reflux surgery in selected cases. |

| Risk of cancer | Higher risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in long-standing disease. | Higher risk of adenocarcinoma in long-standing reflux with Barrett’s esophagus. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Achalasia Cardia

Can achalasia go away on its own?

No, achalasia cardia does not go away on its own. It is a serious disorder resulting from permanent nerve injury in the esophagus. If left untreated, the symptoms usually worsen over time, leading to increasing difficulty swallowing and potential complications like aspiration pneumonia. While treatments can effectively manage symptoms and improve quality of life, the condition itself does not resolve naturally.

Is achalasia cardia hereditary?

Achalasia cardia is generally not considered hereditary or passed down through families. Overall, genetic inheritance is not a common factor in achalasia.

What is the incidence of achalasia cardia?

Achalasia is rare, with studies estimating about 1 new case per 100,000 people each year. It can occur at any age, but most patients are diagnosed between 25 and 60 years old. The condition affects both men and women, although some regional studies suggest a slightly higher occurrence in men.

Is achalasia cardia an autoimmune disorder?

Yes, chronic infection of the food pipe activates an autoimmune antibody response against ganglionic cells, causing loss of neurons and achalasia cardia.

What is the life expectancy with achalasia?

People with achalasia have a normal life expectancy if the disease is diagnosed and treated early. The main concern is difficulty swallowing, which can lead to poor nutrition and weight loss if left untreated. Rarely, long-term achalasia increases the risk of cancer in the esophagus. With modern treatments like surgery or balloon dilation, most patients can eat well and maintain health, reducing complications that could shorten life. Regular check-ups help ensure lasting well-being.

What is the common age group for achalasia cardia?

Achalasia can occur at any age, but it is most often found in adults between 25 and 60 years old. It is less common in children and older adults. The symptoms, such as trouble swallowing and chest discomfort, may appear slowly, causing delays in diagnosis. Although middle-aged adults are most often affected, awareness that it can happen at any age helps doctors identify and treat it earlier, improving patient outcomes and daily life quality.

What is another name for achalasia cardia?

Achalasia cardia is also known by other names such as achalasia, esophageal achalasia, cardiospasm, and esophageal aperistalsis. These terms describe the same condition, a disorder of the esophagus where the muscles and nerves don't work properly, leading to difficulty swallowing and impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter.

What foods are generally recommended to be avoided in cases of achalasia?

People with achalasia cardia are advised to avoid foods that can make swallowing more difficult or worsen symptoms. These include: dry foods such as crackers snacks, bread, or meats that may get stuck in the esophagus. Spicy foods, caffeine, alcohol, and acidic items like citrus fruits or tomatoes can irritate the esophagus and cause discomfort. Carbonated drinks may also worsen chest pressure or reflux.

What causes achalasia cardia in children?

Achalasia in children is caused by damage or loss of nerve cells in the esophagus muscles, especially those controlling the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). This damage leads to the LES failing to relax properly and a lack of normal esophageal muscle contractions, causing swallowing difficulties. Its exact cause is often unknown but may be linked to genetic conditions (like Down syndrome), autoimmune responses, infections, or rare syndromes such as Allgrove syndrome.

Can achalasia cause heart problems?

No, achalasia cardia can never cause heart disease or a condition. But its symptoms can be confused with heart issues. Chest pain from achalasia might feel like angina or a heart attack, which makes some patients go to a cardiologist first. In rare cases, an enlarged esophagus can press on nearby structures, including the heart, causing discomfort or an irregular pulse. These situations are unusual, and heart-related symptoms typically go away after treating the achalasia.

How to differentiate achalasia cardia from carcinoma of the esophagus?

Achalasia cardia can be differentiated by doing special tests like endoscopy, CT scan, esophageal manometry, and biopsy.

What is type 2 achalasia cardia?

Type 2 achalasia cardia is the most common form of achalasia in which pressure builds up inside the esophagus during swallowing, causing the esophagus to become compressed. This happens because the lower esophageal sphincter does not relax properly, preventing food and liquid from entering the stomach. The trapped material increases pressure along the esophagus, often leading to more severe symptoms compared to type 1 achalasia.

Explain the pathology of achalasia cardia?

Achalasia cardia occurs due to the loss of nerve cells in the myenteric plexus of the esophagus, especially those that release nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), which normally help the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relax during swallowing. When these nerves are damaged, the LES stays tightly closed and the esophagus loses its normal wave-like movements (peristalsis). This causes food and liquids to remain in the esophagus, leading to increased pressure, gradual dilation, and inflammation. Long-standing stasis increases the risk of esophageal cancer.

Explain how a barium swallow diagnoses achalasia cardia?

A barium swallow test is commonly used to help diagnose achalasia cardia because it shows how food and liquid move down the esophagus. In this test, the patient swallows a barium-containing liquid, which coats the esophagus and makes it visible on X-rays. In people with achalasia, the X-ray usually shows a dilated esophagus that narrows at the lower end, giving a “bird’s beak” appearance.

When to consult a doctor for achalasia cardia?

Consult a doctor for achalasia cardia if swallowing difficulties are persistent, progressively worse, or interfere with both eating and drinking. Warning signs that require medical attention include:

- Food or liquid coming back up (regurgitation)

- Chest pain or pressure after eating

- Frequent coughing or choking during meals

- Unexplained weight loss

- Nocturnal coughing or aspiration-related chest infections

If these symptoms continue, it is essential to consult a achalasia cardia specialist to confirm the diagnosis and initiate appropriate treatment. Urgent medical attention needs to be sought if sudden breathing difficulty, severe chest pain, or signs resembling a heart attack occur. A gastroenterologist is the specialist who can provide the best achalasia cardia treatment to relieve symptoms and prevent complications.

Share on

Request an appointment

Fill in the appointment form or call us instantly to book a confirmed appointment with our super specialist at 04048486868

Appointment request - health articles

Recent Articles