Helicobacter Pylori (H. Pylori) Infection- Symptoms, Causes, Risk Factors, Treatment & Prevention

PACE Hospitals

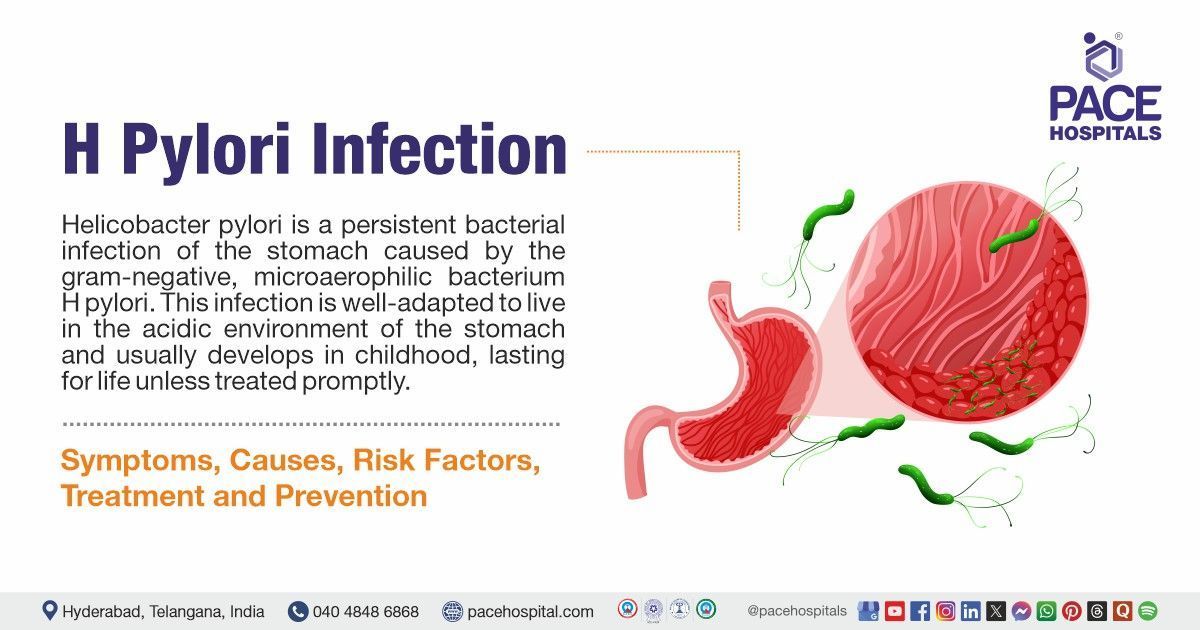

What is H pylori infection?

Helicobacter pylori is a persistent bacterial infection of the stomach caused by the gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium H pylori. This infection is well-adapted to live in the acidic environment of the stomach and usually develops in childhood, lasting for life unless treated promptly.

Most people experience no symptoms, although it can cause abdominal pain, nausea, bloating, loss of appetite, and weight loss if it causes gastritis or peptic ulcers. If left untreated, H. pylori can cause chronic gastritis, peptic or duodenal ulcers, stomach perforation, internal bleeding and an elevated risk of stomach cancer. Healthcare experts, such as primary care physicians or gastroenterologists, manage the diagnosis and treatment, which often includes antibiotics and acid-suppressing drugs.

H pylori meaning

The term "Helicobacter pylori" combines Greek and Latin roots: "Helico-" derives from the Greek "helix", meaning "spiral" or "coil," reflecting the bacterium’s helical shape, while "-bacter" comes from the Greek "baktēria", meaning "rod" or "staff," a common suffix for bacterial names. "Pylori" originates from the Latin "pylorus", meaning "gatekeeper," referencing the pyloric region of the stomach near the duodenum where the bacterium often colonizes.

Initially misclassified as Campylobacter pyloridis in 1983, it was later renamed Campylobacter pylori (1987) before genetic studies prompted its reclassification into the genus Helicobacter in 1989, emphasizing its distinct spiral morphology and gastric habitat.

H. Pylori Epidemiology

Prevalence of H. Pylori infection in world

Helicobacter pylori infection is estimated to affect approximately 43.9% of adults worldwide, with a greater prevalence of 35.1% among children and adolescents. While the prevalence has reduced in adults since around 1990, it is still high in younger age groups. This reduction in adults is especially visible in regions like the Western Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Africa.

Prevalence of H. Pylori infection in India

The frequency of H. pylori infection in India is high, with the frequency ranging from 50% to 80%. This means that a large proportion of the Indian population, including youngsters, is infected with the bacteria. Helico bacter pylori infection is commonly acquired in childhood and can cause several health issues, including gastritis, peptic ulcers, and even stomach cancer.

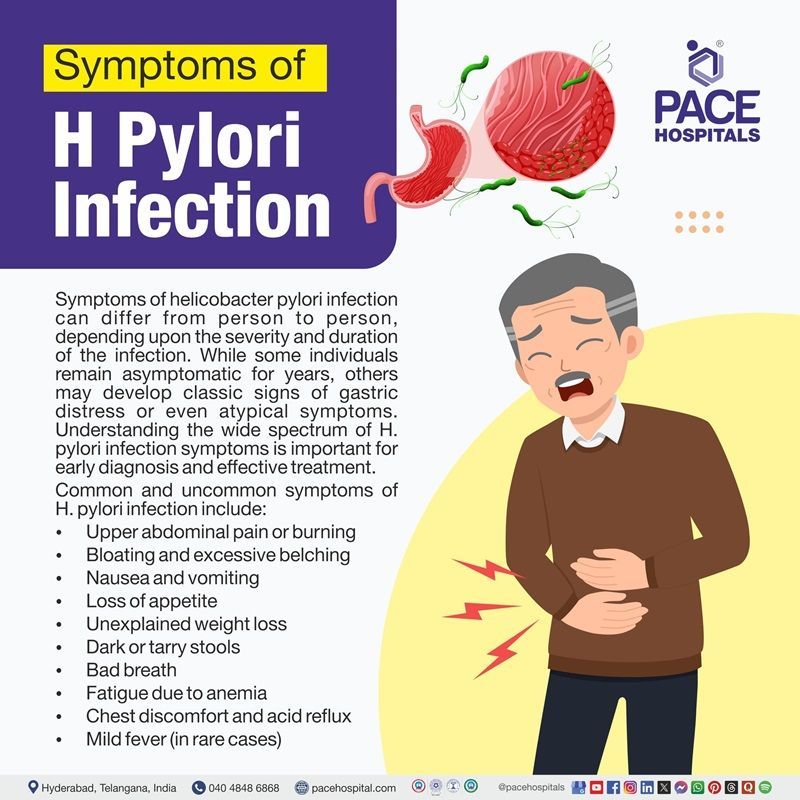

H. Pylori Symptoms

H. Pylori infection symptoms can differ from person to person, depending upon the severity and duration of the infection. While some individuals remain asymptomatic for years, others may develop classic signs of gastric distress or even atypical symptoms. Understanding the wide spectrum of helicobacter pylori symptoms is important for early diagnosis and effective treatment.

Common and uncommon symptoms of H. pylori infection include:

- Upper abdominal pain or burning

- Bloating and excessive belching

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

- Dark or tarry stools

- Bad breath

- Fatigue due to anemia

- Chest discomfort and acid reflux

- Mild fever (in rare cases)

Upper abdominal pain or burning is the hallmark symptom and arises due to the inflammation caused by H. pylori bacteria disrupting the stomach lining. This pain is typically worse on an empty stomach and may improve temporarily after eating.

Bloating and excessive belching occur when the infection interferes with gastric motility and gas builds up in the stomach. These symptoms of H. pylori stomach infection are common, but often overlooked or misattributed to indigestion.

Nausea and vomiting stem from the irritation of the gastric mucosa. In certain individuals, especially those with h pylori positive symptoms, this can lead to recurrent episodes, especially after meals.

Loss of appetite is often a consequence of continuous inflammation and discomfort after eating. This symptom contributes to unintentional weight loss over time.

Unexplained weight loss results from reduced food intake and poor digestion due to damage caused by the bacteria. It is considered one of the red flags among helicobacter pylori infection symptoms.

Dark or tarry stools signal gastrointestinal bleeding, typically from ulcers that form when the stomach lining is eroded. This is one of the serious outcomes that often prompt medical evaluation.

Bad breath, also known as halitosis, can be attributed to the bacterial imbalance and altered gastric acid levels linked to H. pylori colonization.

Fatigue due to anemia occurs when chronic blood loss from ulcerated tissue leads to iron-deficiency anemia, reducing the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

Chest discomfort and acid reflux are considered uncommon symptoms of H. pylori, but they may arise in individuals with esophageal involvement or disrupted gastric emptying.

Mild fever, although rare, has been reported in patients with active infection and systemic inflammatory response. It may appear in conjunction with other systemic symptoms.

In advanced cases, symptoms may resemble those of malignancy. H. pylori stomach cancer symptoms may include persistent abdominal discomfort, extreme fatigue, unintended weight loss, and difficulty swallowing. These signs demand immediate investigation.

Together, these symptoms represent a comprehensive picture of helicobacter pylori symptoms, ranging from mild irritation to serious complications. Being aware of both typical and atypical signs ensures timely medical consultation and better treatment outcomes.

H. Pylori Causes

H. Pylori infection causes are deeply rooted in both environmental and lifestyle conditions that support the transmission and survival of the bacterium. These causes are largely preventable and primarily associated with hygiene and living conditions, making early awareness essential for prevention and control.

H. pylori infection, caused by the Helicobacter pylori bacteria, is a widespread condition often linked to various transmission methods.

Primary causes of H. pylori infection include:

- Contaminated food and water

- Direct contact with saliva or vomit

- Poor hand hygiene

- Shared utensils or personal items

- Inadequate sanitation infrastructure

Contaminated food and water are major sources of infection, especially in areas with poor sanitation. Ingesting this allows the bacterium to enter and colonize the stomach, making contaminated sources a leading entry point for helicobacter pylori causes.

Direct contact with saliva or vomit can transmit the bacteria through kissing or sharing drinks with infected individuals, a common pathway among interpersonal H. pylori infection causes.

Poor hand hygiene, especially before meals or after bathroom use, increases the risk of fecal-oral transmission of the pathogen and is one of the most underestimated helicobacter pylori infection causes.

Shared utensils or personal items such as toothbrushes or cups facilitate person-to-person spread within households, especially where communal eating practices are involved—highlighting household dynamics in H. pylori bacteria causes.

Inadequate sanitation infrastructure, including lack of clean water supply and sewage systems, is a systemic cause of widespread infections in lower-income regions and remains one of the most persistent H. pylori infection causes globally.

At the core of these issues lies a combination of environmental, behavioral, and systemic shortcomings. Understanding and addressing these helicobacter pylori infection causes can help curb transmission and reduce the burden of disease.

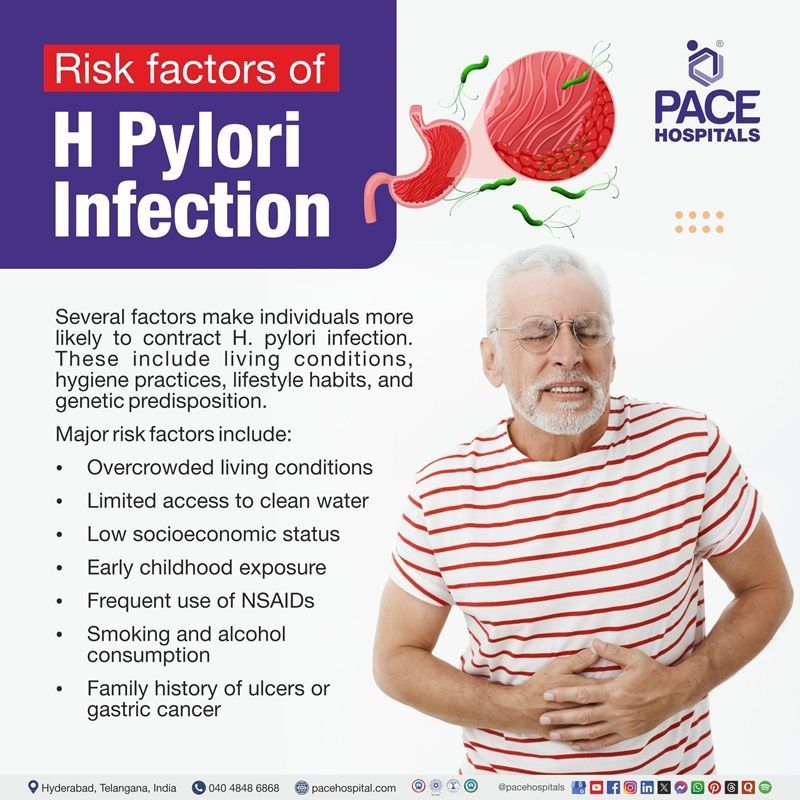

Risk factors for H. Pylori Infections

Several factors make individuals more likely to contract H. pylori infection. These include living conditions, hygiene practices, lifestyle habits, and genetic predisposition.

Major risk factors include:

- Overcrowded living conditions

- Limited access to clean water

- Low socioeconomic status

- Early childhood exposure

- Frequent use of NSAIDs

- Smoking and alcohol consumption

- Family history of ulcers or gastric cancer

Overcrowded living conditions facilitate close contact and increase the risk of bacterial transmission through shared spaces and objects.

Limited access to clean water makes it difficult to avoid ingesting contaminated water, which is a known vector for H. pylori.

Low socioeconomic status is linked to reduced access to healthcare, sanitation, and education about infection prevention.

Early childhood exposure is common in endemic areas, where children contract the bacteria at a young age and carry it for life if untreated.

Frequent use of NSAIDs can weaken the stomach’s protective lining, making it more vulnerable to colonization and damage by the bacterium.

Smoking and alcohol consumption both impair the stomach’s ability to heal and defend itself, exacerbating the effects of infection.

Family history of ulcers or gastric cancer suggests possible genetic vulnerability and shared environmental exposures, increasing the likelihood of infection and complications.

H. Pylori Pathogenesis

Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis involves a series of complex interactions between the bacterium and the gastric mucosa. Once inside the stomach, the bacterium uses its flagella to burrow into the protective mucous layer of the stomach lining. This strategic movement shields it from the acidic gastric environment and brings it into close contact with epithelial cells.

An essential step in its survival is the production of the enzyme urease, which breaks down urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. This localized production of ammonia neutralizes the surrounding stomach acid, allowing H. pylori to establish a stable environment for colonization.

Once adhered to the stomach lining, H. pylori releases a range of virulence factors. Among the most notable are:

CagA (cytotoxin-associated gene A): Once injected into host cells, CagA H pylori disrupts cellular signaling, promotes inflammation, and is associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer.

VacA (vacuolating cytotoxin A): This VacA H pylori toxin interferes with cell structure and immune responses, promoting cell death and weakening host defenses.

The persistent presence of these virulence factors causes chronic inflammation, leading to damage to the epithelial cells and loss of mucosal integrity. Over time, this can result in gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and, in some cases, progression to malignancy. The immune system is unable to clear the infection, contributing to its long-term persistence.

Understanding the pathogenesis of H. pylori is essential in appreciating how a seemingly silent infection can lead to significant gastrointestinal diseases. This insight forms the basis for clinical strategies aimed at early diagnosis, targeted therapy, and long-term monitoring.

Complications of H. Pylori Infection

Complications arising from H. pylori infection can range from mild to life-threatening conditions. These complications are a result of persistent inflammation, damage to the gastric lining, and prolonged colonization of the stomach by H. pylori.

Possible complications include:

- Peptic ulcers

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Atrophic gastritis

- Gastric adenocarcinoma

- MALT lymphoma (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma)

- Iron-deficiency anemia

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

Peptic ulcers occur when H. pylori damages the protective mucous barrier of the stomach or duodenum, allowing acid to erode the underlying tissue. This leads to painful sores that may cause burning abdominal pain, especially on an empty stomach.

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a consequence of ulceration that affects blood vessels. When an ulcer deepens and erodes a vessel, it may cause blood to appear in vomit or stool, potentially leading to anemia.

Atrophic gastritis develops after prolonged inflammation that causes thinning of the stomach lining. This impairs the stomach’s ability to produce acid and enzymes, hindering digestion and nutrient absorption.

Gastric adenocarcinoma is one of the most severe outcomes. Chronic inflammation caused by H. pylori leads to cellular changes and DNA damage, increasing the risk of cancer in the stomach lining, particularly in individuals with a genetic predisposition.

MALT lymphoma, a rare form of stomach cancer, originates from immune cells in the gastric mucosa. Interestingly, this condition can regress with successful H. pylori eradication, especially in early stages.

Iron-deficiency anemia may result from chronic, unnoticed blood loss due to ulceration. This condition reduces red blood cell production and can cause fatigue, pallor, and shortness of breath.

Vitamin B12 deficiency arises because a damaged stomach lining may not produce intrinsic factor, a protein essential for B12 absorption. This leads to neurological symptoms and worsening fatigue if not corrected.

Timely treatment of H. pylori infection significantly reduces the likelihood of complications associated with h pylori and is crucial for maintaining long-term gastrointestinal health.

It is especially important to recognize the complications of H. pylori in children, who may present with slower growth, abdominal pain, or anemia symptoms that are often misattributed to other childhood conditions.

When identified early, these H. pylori complications are often manageable and reversible.

H. pylori Diagnosis

Accurate helicobacter pylori infection diagnosis is crucial for initiating timely and effective treatment. Most infections are diagnosed when patients present with gastrointestinal symptoms, such as persistent dyspepsia, but many cases are detected through screening, particularly in high-risk individuals. Several reliable methods are available to confirm the presence of the bacterium.

Common diagnostic methods include:

- Urea breath test

- Stool antigen test

- Blood antibody test

- Endoscopy with biopsy

Urea breath test is a non-invasive and widely used method. The patient swallows a urea solution labeled with a carbon isotope. If H. pylori is present, it breaks down the urea and releases carbon dioxide, which is then detected in the patient’s breath. This test is highly accurate and especially useful for confirming eradication after treatment.

Stool antigen test detects H. pylori proteins in a fecal sample. It is also non-invasive and considered reliable for both initial diagnosis and post-treatment follow-up.

Blood antibody test checks for the presence of antibodies against H. pylori. While it can indicate past or present infection, it is less preferred because it cannot distinguish between an active infection and one that has been previously treated.

Endoscopy with biopsy is usually reserved for patients with severe symptoms, suspected ulcers, or gastrointestinal bleeding. A flexible tube with a camera is inserted into the stomach to collect tissue samples for histological examination, culture, or a rapid urease test.

The choice of test depends on the clinical presentation, patient age, and risk factors. For instance, invasive tests are preferred when malignancy or complicated ulcers are suspected. A confirmed diagnosis enables clinicians to initiate the appropriate H. pylori treatment options, increasing the chances of full recovery.

H. Pylori Treatment

Helicobacter pylori treatment involves a structured regimen using a combination of medications that aim to eliminate the bacteria and promote mucosal healing. These regimens generally consist of antimicrobials paired with acid-suppressing agents to enhance therapeutic effectiveness and minimize resistance.

Common treatment options include:

- Triple therapy

- Quadruple therapy

- Sequential therapy

- Bismuth-based combinations

Triple therapy involves the use of two different classes of antibiotics along with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). The acid suppression created by the PPI enhances the effect of the antibiotics and facilitates ulcer healing. This combination is typically the first choice in uncomplicated cases. In many clinical settings, triple therapy is also available in the form of a H pylori kit, which packages the medications together for improved convenience and adherence.

Quadruple therapy includes a PPI, a bismuth compound, and two different classes of antibiotics. It is often preferred in regions with higher antibiotic resistance or in patients who have failed previous treatment attempts.

Sequential therapy administers one class of antibiotics in the initial phase followed by a different class in the second phase, accompanied by acid suppression throughout. This strategy aims to maximize bacterial eradication and limit resistance development.

Bismuth-based combinations are particularly effective in cases with confirmed resistance or penicillin allergies. These regimens combine bismuth salts with a PPI and antimicrobial agents from two different classes.

The typical course lasts 10 to 14 days, and adherence is critical to avoid treatment failure and the development of antibiotic resistance. Patients are advised to complete the full course even if symptoms improve early. A follow-up test, usually a urea breath test or stool antigen test, is recommended for four to six weeks after treatment to confirm eradication.

The typical course lasts 10 to 14 days, and adherence is critical to avoid treatment failure and the development of antibiotic resistance. Patients are advised to complete the full course even if symptoms improve early. A follow-up test, usually a urea breath test or stool antigen test, is recommended for four to six weeks after treatment to confirm eradication.

H. Pylori Prevention

Helicobacter pylori prevention focuses on minimizing exposure to the bacterium through improved hygiene and food safety practices. While no vaccine exists currently, several behavioral strategies can significantly reduce the risk of infection.

- Preventive strategies include:

- Practicing proper hand hygiene

- Drinking clean and safe water

- Consuming well-cooked and hygienically prepared food

- Avoiding sharing utensils or drinks

- Improving public sanitation infrastructure

Hand hygiene is the most effective way to prevent fecal-oral transmission. Washing hands with soap and clean water before meals and after using the toilet significantly lowers the risk of infection.

Safe water consumption involves drinking boiled, filtered, or bottled water, especially in areas where water quality is questionable. Avoiding untreated tap water is especially crucial in rural and developing regions.

Proper food preparation includes cooking meat thoroughly, washing fruits and vegetables with clean water, and maintaining hygienic kitchen practices. This helps avoid ingesting contaminated food.

Avoiding shared utensils reduces person-to-person transmission. This is particularly important within families where one or more members may unknowingly carry the infection.

Public sanitation improvements, such as better sewage disposal and access to clean water, play a significant role in reducing population-level prevalence.

While individual prevention is vital, broader public health interventions can drastically reduce the burden of disease in endemic regions. Ongoing research into vaccine development may eventually provide an additional layer of protection against H. pylori infection.

Difference Between H. Pylori and SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth)

H. Pylori vs SIBO

While both H. pylori and SIBO involve bacterial imbalances in the gut, they affect different areas and require distinct management. Below are six major differences:

| Aspect | H pylori infection | SIBO |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Stomach (gastric mucosa) | Small intestine |

| Cause | Bacterial infection (H. pylori gram-negative bacterium) | Overgrowth of normal gut bacteria |

| Primary Symptoms | Stomach pain, nausea Bloating, burping Ulcers, gastritis | Abdominal distension Diarrhea/constipation Malabsorption (e.g., vitamin deficiencies) |

| Diagnosis | Urea breath test, Stool antigen test & Endoscopy with biopsy | Lactulose/glucose breath test Small bowel aspirate (gold standard) |

| Treatment | Antibiotics along with proton pump inhibitors | Antibiotics + Dietary changes |

| Complications | Peptic ulcers, Gastric cancer & Chronic gastritis | Nutrient deficiencies (B12, iron), Leaky gut & IBS-like symptoms |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on H. Pylori

How to get rid of H. pylori?

H. pylori is typically eradicated using a combination of antibiotics and acid-suppressing medications, known as triple or quadruple therapy. Treatment should be prescribed and monitored by a healthcare professional to ensure complete eradication and reduce resistance. The regimen usually lasts 10–14 days, and adherence is crucial for success. Follow-up testing is recommended to confirm the infection is cleared.

Can H. pylori come back?

H. pylori infection can recur if not fully eradicated or if re-exposure occurs, but recurrence after successful treatment is uncommon in areas with good hygiene and sanitation. Reinfection rates are higher in regions with poor sanitation. Proper follow-up testing ensures successful eradication. Maintaining good hygiene reduces the risk of reinfection.

Is H. pylori hereditary?

H. pylori infection is not hereditary but is often acquired in childhood through close contact with infected family members, especially in crowded or unsanitary conditions. The risk is higher in families where hygiene is compromised. Genetics do not play a direct role in transmission. Prevention focuses on improving sanitation and hygiene.

Can H. pylori cause cancer?

Yes, chronic H. pylori infection significantly increases the risk of gastric cancer, including gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma. It is classified as a type I carcinogen by the WHO. Early detection and treatment reduce cancer risk. Regular monitoring is recommended for high-risk individuals.

Can H. pylori be cured?

Yes, H. pylori infection can be cured with appropriate antibiotic therapy combined with acid suppression. Successful eradication is confirmed with follow-up testing after treatment. Completing the full course of medication is essential for cure and to prevent antibiotic resistance. Most patients achieve cure with first-line therapy, but some may require alternative regimens.

What does H. pylori poop look like?

H. pylori infection does not have a specific appearance in stool. However, in severe cases with ulcers or bleeding, stool may appear black and tarry due to digested blood, indicating gastrointestinal bleeding. Most people with H. pylori will have normal-looking stool, as the infection affects the stomach lining rather than the intestines. Diagnosis of H. pylori is not made by stool appearance but through specific laboratory tests.

What are the first symptoms of H. pylori?

The first symptoms of H. pylori infection often include abdominal pain or discomfort, bloating, nausea, loss of appetite, frequent burping, and sometimes vomiting. Many people remain asymptomatic or have mild symptoms in the early stages. Symptoms may worsen over time if the infection causes gastritis or ulcers. Early detection and treatment can prevent complications.

Is H. pylori dangerous?

H. pylori can be dangerous if left untreated, as it increases the risk of developing peptic ulcers, chronic gastritis, and gastric cancer, including gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma. Persistent infection can lead to serious complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation. Early treatment significantly reduces these risks. Regular monitoring is important in high-risk individuals.

What is H. pylori test?

H. pylori can be detected using several tests, including urea breath tests, stool antigen tests, endoscopic biopsy with histology, and blood antibody tests. The urea breath and stool antigen tests are commonly used for diagnosis and confirmation of eradication. Endoscopic biopsy is reserved for complex cases or when ulcers are suspected. Each test has specific indications and accuracy levels.

How does H. pylori spread?

H. Pylori spreads mainly through person-to-person contact via oral-oral, fecal-oral, or gastric-oral routes, including contact with saliva, stool, or vomit. It is often acquired in childhood, especially in areas with poor sanitation. Crowded living conditions and contaminated food or water increase the risk of transmission. Good hygiene practices can help prevent infection.

Can ultrasound detect H. pylori?

Ultrasound cannot detect H. pylori infection. Diagnosis relies on specific tests such as urea breath, stool antigen, or endoscopic biopsy, not imaging. Ultrasound may be used to assess complications like ulcers or masses but cannot identify the bacteria itself. Accurate diagnosis requires laboratory-based or endoscopic methods.

Can H. pylori be tested by blood?

Blood tests can detect antibodies to H. pylori, indicating past or current infection. However, they are less accurate for confirming active infection or eradication compared to stool antigen or breath tests. Antibodies may persist after successful treatment, leading to false positives. Blood tests are mainly used where other methods are unavailable.

Can H. pylori cause fever?

Fever is not a typical symptom of H. pylori infection. Most patients present with gastrointestinal symptoms rather than systemic symptoms like fever. If fever occurs, it may indicate complications such as perforation or another infection. Medical evaluation is necessary if fever accompanies digestive symptoms.

Can H. pylori cause high blood pressure?

There is no established evidence linking H. pylori infection directly to high blood pressure. Its main effects are on the gastrointestinal system. Some studies have explored possible indirect associations, but no causal relationship has been proven. Management of H. pylori does not impact blood pressure control.

Can H. pylori cause urinary problems?

H. pylori primarily affect the stomach, but some studies suggest a possible association with urinary stones in children. However, it is not a recognized cause of urinary tract infections (UTI) or typical urinary problems. Most urinary symptoms are unrelated to H. pylori infection. Further research is needed to clarify any indirect associations.

Can H. pylori cause white tongue?

H. Pylori infection is not known to directly cause a white tongue. White tongue is usually related to oral hygiene or other oral conditions. While some studies have explored links between oral and gastric bacteria, there is no conclusive evidence connecting H. pylori to this symptom. Oral symptoms should be evaluated separately by a healthcare expert.

Does H. pylori cause IBS?

There is no conclusive evidence that H. pylori cause irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The infection is mainly associated with upper gastrointestinal symptoms and diseases. Some studies have examined a possible link, but findings are inconsistent. IBS is a separate condition with different underlying mechanisms.

Does H. pylori cause weight gain?

H. pylori infection is not associated with weight gain. In some cases, it may cause loss of appetite and unintentional weight loss due to gastrointestinal discomfort. Chronic infection can lead to malnutrition if left untreated. Weight changes should be evaluated for other causes if present.

Is HPV and H. pylori the same?

HPV (human papillomavirus) and H. pylori (Helicobacter pylori) are not the same. HPV is a virus causing warts and cancers, while H. pylori is a bacterium causing stomach infections. They affect different body systems and require different treatments. Confusion between the two can delay proper diagnosis and care.

Is lemon good for H. pylori?

There is no scientific evidence from peer-reviewed studies or government sources that lemon can cure or treat H. pylori infection. Medical treatment with antibiotics is required. Some home remedies may provide temporary symptom relief but do not eradicate the bacteria. Relying solely on natural remedies can lead to complications.

Can H. pylori cause UTI infection?

H. pylori is not a recognized cause of urinary tract infections (UTIs), though some studies suggest a possible link to urinary stones in children. The bacteria primarily affect the stomach lining. Most UTIs are caused by other bacteria such as E. coli. H. pylori testing is not indicated for urinary symptoms.

Can H. pylori cause acid reflux?

H. Pylori infection can influence gastric acid secretion and may be associated with changes in acid reflux symptoms, but it is not a direct cause of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Some studies suggest eradication may improve or worsen reflux symptoms in certain individuals. The relationship is complex and varies by patient. Treatment should be individualized based on symptoms and risk factors.

Share on

Request an appointment

Fill in the appointment form or call us instantly to book a confirmed appointment with our super specialist at 04048486868

Appointment request - health articles

Recent Articles